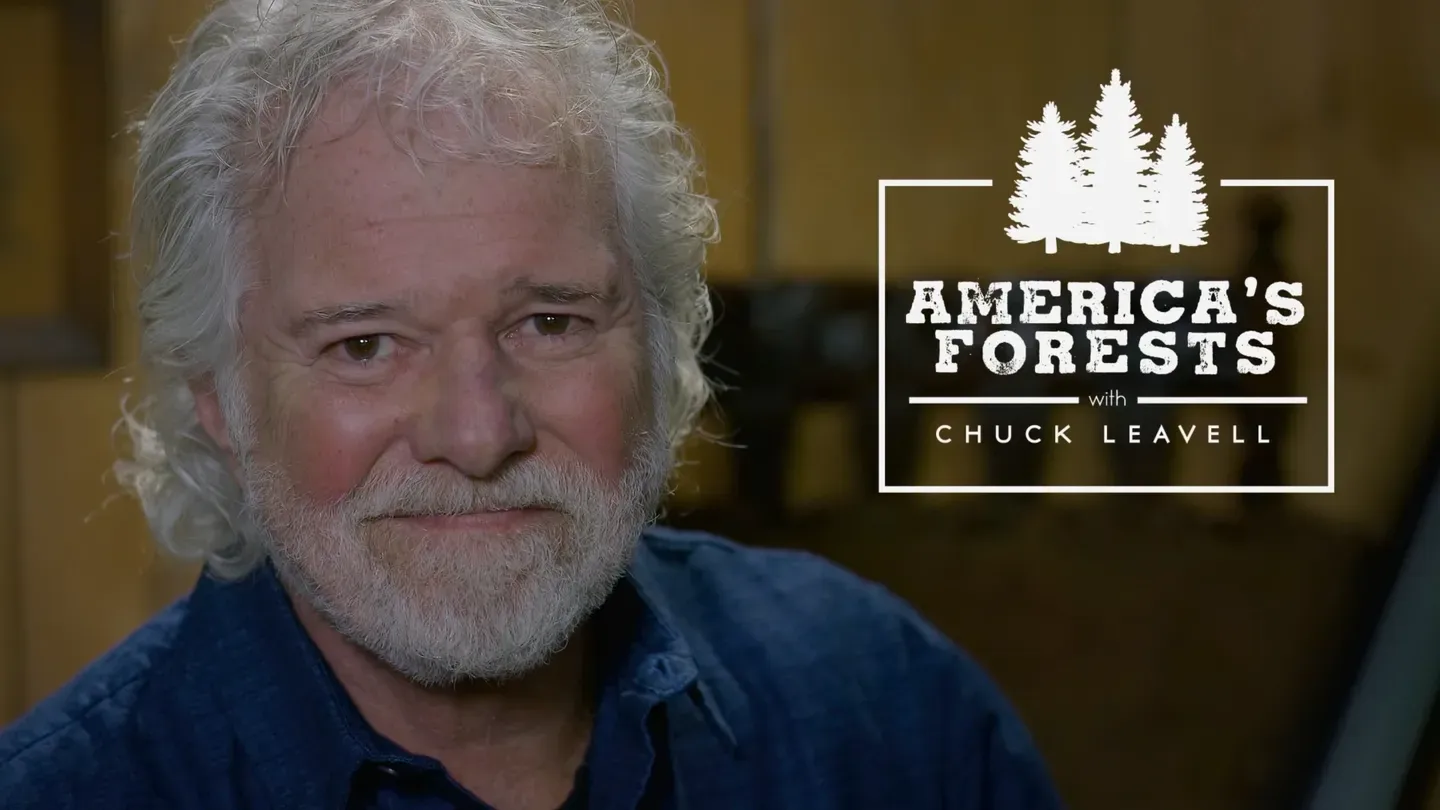

America's Forests with Chuck Leavell

Colorado

Episode 2 | 26m 47sVideo has Closed Captions

In this episode, we travel to Colorado.

In this episode, we travel to Colorado. We follow the path of clean drinking water from forests to faucets. We discover the innovative ways that Coloradans are embracing beetle-kill wood. And we discover the gift of peace that comes to military veterans from fly-fishing in mountain streams.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

America's Forests with Chuck Leavell is a local public television program presented by RMPBS

America's Forests with Chuck Leavell

Colorado

Episode 2 | 26m 47sVideo has Closed Captions

In this episode, we travel to Colorado. We follow the path of clean drinking water from forests to faucets. We discover the innovative ways that Coloradans are embracing beetle-kill wood. And we discover the gift of peace that comes to military veterans from fly-fishing in mountain streams.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch America's Forests with Chuck Leavell

America's Forests with Chuck Leavell is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipCHUCK LEAVELL: On the next episode of America's Forests with me, Chuck Leavell, I travel to Colorado.

Here you can feel the powerful connection between the natural world and daily life.

From the forests high in the Rockies that provide healthy drinking water to millions of people, to the innovative way people are using beetle-kill wood, to the gift of peace that comes from fly fishing for mountain trout with military veterans.

CHUCK LEAVELL: Hi, I'm Chuck Leavell.

You know, in addition to my beautiful family, there's two things in my life that I have a special interest in and love for: Music and trees.

My wife, Roselane and I own and manage our own forest land right here in Georgia, Charlane Plantation.

We grow Southern yellow pine, as well as other species here.

And you know, as I get to travel the world with the Rolling Stones or some of the other artists that I'm so privileged to work with, I get to meet all kind of folks that also have a passion and love for trees, forests, and the outdoors.

And now, I get to share their stories with you.

So join me as we journey through America's Forests.

♪MUSIC CHUCK LEAVELL: Here we are -- Loveland Pass, Colorado, some 12,000 feet above sea level, right on the Continental Divide.

And as you can tell, well, it's a little bit windy up here today.

Well, this whole area is known as ski country, but you know what?

It's also known as water country.

CHUCK LEAVELL: Why?

Because in the winter the snows come and they blanket all these mountains and then in late spring and throughout the summer, the snow melt happens and the water runs all the way down through these beautiful healthy, pristine forests, down into the rivers and the valleys below.

Eventually all the way to Denver and the Metropolitan area, and what does that do?

That provides all of those inhabitants and visitors with clean, pristine water.

Colorado is home to 11 national forests and the headwaters of four major rivers the Colorado, the Arkansas, the Rio Grande and the Platte.

Acres and acres of trees are actively managed to provide drinking water to tens of millions people in the West, all the way from Colorado to Mexico.

CHUCK LEAVELL: Scott, this is just breathtaking.

It's just so gorgeous man.

Tell me exactly where we are.

SCOTT FITZWILLIAMS: We're on the White River National Forest, and uh, and, just above Keystone.

This is Snake River here, and uh...it's an area that we've been doing a lot of work in the forest; we've done a lot of restoration work.

You know what people often think about, you know, when they see the forest, they often don't either understand or think about the relationship between forest and water.

CHUCK LEAVELL: Yeah.

SCOTT FITZWILLIAMS: And that's probably the most important thing we're working on.

SCOTT FITZWILLIAMS: A lot of people don't realize when they look to the mountains - that's where their water's coming from.

They think it comes out of the faucet and it comes from the forest.

CHUCK LEAVELL: But getting that water from the mountains to the cities is a complex process.

The first challenge is the Continental Divide.

TERRY BAKER: We're sitting here on the west side of the Continental Divide, it divides the country into-- basically into the Pacific into-- basically into the Pacific The water comes from the west side, crosses over to the east side, back to the west side, and then back over to the east side to these reservoirs.

and then back over to the east side to these reservoirs.

TERRY BAKER: The water starts out It all collects, runs through these siphons TERRY BAKER: There are no pumps.

TERRY BAKER: This project was completed somewhere around 1918, so the early 1900s.

It's been around almost 100 years at this point.

It's been around almost 100 years at this point.

And really it does just showcase some forethought as far And really it does just showcase some forethought as far as the implementation and putting this in place.

as the implementation and putting this in place.

Despite all the engineering and architectural ways Despite all the engineering and architectural ways we've moved forward in the past almost hundred years we've moved forward in the past almost hundred years CHUCK LEAVELL: More than 2000 miles of pipe criss-crosses the Continental Divide as they transport mountain-born water to ten reservoirs as they transport mountain-born water to ten reservoirs as they transport mountain-born water to ten reservoirs scattered around the city.

scattered around the city.

I'm getting an exclusive look at one of them, courtesy of Christina Burri, watershed scientist courtesy of Christina Burri, watershed scientist at Denver Water.

at Denver Water.

CHRISTINA BURRI: This is the Strontia Springs Reservoir that supplies water for about 1.4 million people.

CHUCK LEAVELL: The word awesome is over used I'm sure but I got to say this is awesom.

CHRISTINA BURRI: About 90% of our water moves through this reservoir.

So it's very, very important to Denver Water.

CHUCK LEAVELL: You know, Christina, You know, you're looking at all these rocks You know, you're looking at all these rocks and strong mountains, but I think and strong mountains, but I think there's probably more to the story than what you see.

CHRISTINA BURRI: There is.

and they don't realize how vulnerable it is.

CHUCK LEAVELL: Vulnerable especially to wildfires, in 2002, the reservoirs in the Denver Water system were hit hard, when the Hayman fire ripped through the region.

CHRISTINA BURRI: Smoke, ash, everything was black, the soil was just completely burned, sterilized.

CHRISTINA BURRI: It was approximately 138,000 acres.

CHUCK LEAVELL: How long a period of time did that happen?

CHRISTINA BURRI: It was over half of the summer it burned.

CHUCK LEAVELL: And so after that incredible event of the Hayman fire, I think there was some flooding, is that right?

CHRISTINA BURRI: There was significant floods.

And because of the fire, and the loss of vegetation holding that soil back, all of that soil eroded and washed downstream into our reservoirs.

And we had one million cubic yards of sediment.

A lot of the cost of reacting to these high intensity fires, like the Hayman, was to remove all that debris.

CHRISTINA BURRI: This landscape, as strong as it looks, it's prone to these really high intensity fires.

It's overly dense.

By restoring the forests, it's helping improve our--our water.

CHUCK LEAVELL: The Hayman Fire was a wake up call, making it clear both to Denver Water and the US Forest Service that watershed health was a top priority.

Since then, they have partnered on prescribed burning, fighting invasive species, and replanting trees on both public and private lands.

CHUCK LEAVELL: To see if those efforts are paying off requires regular testing of water.

So I caught up with a local non-profit that is bringing young people out to the rivers to literally get their feet wet.

CHUCK LEAVELL: All right.

And thank you so much for inviting me out here to do this with you.

And by the way, I want to show I am part of the team today.

Yes!

RACHEL HANSGEN: Thank you for being here.

CHUCK LEAVELL: It s great!

RACHEL HANSGEN: So, we are right now at the confluence of Bear Creek and the South Platte river.

RACHEL HANSGEN: Most of us, um, tend to forget that we are connected to all of the big, majestic places that are in our back country, connected to our backyards.

CHUCK LEAVELL: And uh, what are we gonna be doing?

We're gonna be taking some samples?

RACHEL HANSGEN: You are going to be a fine crew member.

RACHEL HANSGEN: You're gonna be taking some samples, getting some flow measurements.

Um, you're gonna see what a day in the field looks like for our high school students and our Metro State University students.

RACHEL HIMYAK: There we go ... just resting on the very top, like that.

CHUCK LEAVELL: Ok, all right.

RACHEL HIMYAK: Now we can look up here and read our depth.

So we can estimate it to be about 13 inches deep.

So, we call that one out, and I'd say, "13 inches."

ALEX STEVER: 13 inches.

CHUCK LEAVELL: So, Rachel, why do we even care about doing this?

I mean, what does it mean to you to test this water quality, the flow, and all the different data that we're getting.

RACHEL HIMYAK: What we were working on mostly for this, is looking for bacteria in the water, specifically E. Coli, which is an indicator of human poo in the water, which is not necessarily a good thing.

CHUCK LEAVELL: No.

RACHEL HIMYAK: So, I'm sure upstream, especially the forests and a lot of the growth and things like that will really help filter a lot of the bacteria coming through, algae, things like that.

Which makes it a lot cleaner downstream and allows this water to used for recreational purposes.

CHUCK LEAVELL: Excellent.

There you go.

CHUCK LEAVELL: All right.

So I am here with my new pal Triland.

And Triland, what in the heck are we doing here?

TRILAND MCCONICO: We have, uh, three bottles.

One is a DNA sample, another one is E.coli sample and this is a turbidity sample.

CHUCK LEAVELL: Turbidity??

TRILAND MCCONICO: Yes, it's basically to tell how foggy or how clear the water is within the creek.

CHUCK LEAVELL: Ok, clear or foggy.

I can, I can get there.

I'm learning!

(laughs) TRILAND MCCONICO: What I like about the work is it gives us a chance to come out here and help our environment.

It gives us a chance to help the people that like to come out here for the recreational use, you know, stay safe, just makes it a lot healthier, more vivid, because we're actually out here doing something for the environment.

CHUCK LEAVELL: The last stop on my journey is the Marston Water Treatment Plant, where manager Patty Brubaker guides me through a maze of machinery.

PATTY BRUBAKER: So the Marston Water Treatment facility can do 250 million gallons a day.

But Denver itself in the summer uses about 300 million gallons of water.

PATTY BRUBAKER: --million gallons CHUCK LEAVELL: --in 24 hours!

PATTY BRUBAKER: Yes.

CHUCK LEAVELL: When people see all this, all this mechanics, all these pipes and switches and valves and everything, I think that's probably what they envision when they think of a filtration system, but, the filtration doesn't begin here, does it?

PATTY BRUBAKER: No, it doesn't.

In fact, what's really key to water treatment is the source water coming in.

And Denver Water is so lucky, because we have pristine water source.

And that is because of our watersheds.

CHUCK LEAVELL: Thank you trees and forests.

PATTY BRUBAKER: Thank you.

Without them, it'd be really difficult.

CHUCK LEAVELL: This is the final phase of the operation?

The filtration phase?

Man, you know what?

This looks like that thing, that when they made Frankenstein.

You know, do I get to push this?

PATTY BRUBAKER: You do.

CHUCK LEAVELL: I'm so excited.

It's alive!

It's alive!

CHUCK LEAVELL: From Forests to Faucets, it's so simple and so true.

A healthy forest is good 'till the last drop.

CHUCK LEAVELL: In recent years Colorado has experienced a terrible outbreak of the mountain pine beetle.

It's literally decimated millions of acres of forest land.

But the good news is some very creative people have some really beautiful things out of that beetle kill wood.

Fine furniture, skis, objects of art, and even musical instruments.

CHUCK LEAVELL: I'm here at Hideaway Studios, in the mountains halfway between Denver and Colorado Springs.

I've come to meet up with four local musicians.

On bass - Mark Diamond.

On guitar, Wendy Woo ... and Paul Preziosi.

And on drums, Christian Teele.

WENDY WOO: Well I do a lot of guitar percussion pieces.

I call it slaptap where you use the body of the guitar.

So it's built out of beetle kill here.

and then he's got a goat skin on the head, so it's kind of a drum/guitar.

CHUCK LEAVELL: And Christian's playing the cajon.

Tell us about this particular one you're on here.

CHRISTIAN TEELE: So this is made by the same maker, Dan Bouillez, who made the guitar.

He s got gorgeous coloring.

He tries to get one board for the whole drum, so you get some color themes that carry throughout.

And it's just got a great big huge bass tone.

(plays drum) CHUCK LEAVELL: These unique instruments were hand-crafted by Dan Bouillez using beetle kill pine from Colorado's Rocky Mountains.

DAN BOUILLEZ: It's great wood.

It's beautiful to look at and sounds amazing in these drums.

DAN BOUILLEZ: there's a noticeable difference between each drum I build.

Not only does every one of them look different, but every one of them sounds slightly different, has a different tone, whether it's a higher or a lower tone, it's got more bass or less bass.

DAN BOUILLEZ: I believe the wood is what makes the difference.

It's got a warmer tone to it, it's not so, uh, snappy, I don't know how else to explain it, but, uh, after they've had it for a month and played it for a while, it's like they won't play anything else.

CHUCK LEAVELL: Colorado's beetle epidemic is recent but the story of beetles and trees is ancient.

JOHN TWITCHELL: Mountain pine beetles are a native insect species that have been with us since the ice age, 11,000 years ago.

So, a very natural component of the forest.

JOHN TWITCHELL: My name is John Twitchell.

And I'm a District Forester for the Colorado State Forest Service.

JOHN TWITCHELL: The mountain pine beetle is not very big, and I actually have some with me.

They're about the size of a grain of rice, or so.

CHUCK LEAVELL: But those tiny insects wreaked massive damage, triggering an epidemic about 15 years ago.

JOHN TWITCHELL: Something was different about this epidemic.

We were starting to come out of a drought, but it had been a multiyear drought starting in the early 2000s.

And that really stressed the trees.

So, the beetles started doing what the beetles do, which is increase their population in response and start feeding on these trees.

That combined with some fairly mild winters, all of a sudden this thing started increasing exponentially.

JOHN TWITCHELL: The vast majority of our Lodgepole pine stands--mature Lodgepole pine stands-- were affected.

We had up to ninety, and even a hundred percent mortality.

CHUCK LEAVELL: The forests in Colorado have faced a double whammy - mountain pine beetles and spruce beetles.

MOLLY PITTS: One of the things that the spruce beetle epidemic has proven is that it crosses all boundaries.

Doesn t care if it s national forest, private lands, doesn t care if it s timber land or recreational land.

When you have an epidemic as large as our spruce beetle epidemic here in Colorado, we need to do some management, for potential fire breaks in future, for habitat and also for our recreational use.

MOLLY PITTS: The salvaging around here directly provides jobs to some of our rural communities which is really important.

And it also becomes a marketable product that people buy each and every day.

CLAY SPEAS: We're in the, uh, yard of Montrose Forest Products in Montrose, Colorado.

Uh, this is one of the larger mills in this area.

CLAY SPEAS: You do have everything from the timber industry who'd like to harvest trees to maintain a product to keep mills open, you also have the conservation community that's more interested in terms of preservation, and so with collaboration, means you bring all those different interests together and you work together to reach a common goal.

CHUCK LEAVELL: From conservationists to harvesters to builders, everyone had to learn to embrace beetle-kill wood.

CHUCK LEAVELL: So Bill, this is one of the beetle-kill, uh, what is that, 2x6?

CHUCK LEAVELL: You can see that blue stain right here, going this side of the edge.

And then you see a little bit more of the roughness and the coloration here.

And I understand that when you started using this in some of these housing projects, that there was a little bit of resistance.

BILL RECTANUS: There was.

We worked real hard to be a part of developing the market for this.

Uh, funny story, the initial load of lumber that we had to bring to town.

We had to commit to buying the whole truck load because there was so much concern about the quality of the material.

The truth is, that once the lumber yard saw it, and once the framers started using it, they're thrilled to use it.

Truer, straighter, and cleaner to use, than most of the traditional lumber they were used to.

CHUCK LEAVELL: And even ski-makers have gotten on board the beetle-kill bandwagon, like Meier Skis in Downtown Denver.

CHUCK LEAVELL: I love this sign and you know why?

Because it says handmade skis from Colorado trees.

CHUCK LEAVELL: Alright, we re gonna line this up.

Okay.

Let's line these up.

This one.

Alright.

Got it!

TYLER SILVERMAN: Good to go!

TYLER SILVERMAN: Now all we need is that call sheet and then we'll throw a heat blanket on.

TYLER SILVERMAN: You're pressing a ski.

CHUCK LEAVELL: I'm doin' it, man!

I'm a ski-maker!

TYLER SILVERMAN: You're a ski-maker.

CHUCK LEAVELL: From skis to another favorite Colorado past-time, having a beer.

I sat down with Governor John Hickenlooper and Luis Benitez of the state's outdoor recreation office to talk about the challenges brought on by explosive growth.

CHUCK LEAVELL: Cheers!

CHUCK LEAVELL: You're experiencing incredible growth here.

You know, it's just amazing.

I come from Georgia, Atlanta has a similar problem.

LUIS BENITEZ: That's really the question that's in front of us right now with this immense growth.

People are coming here because they want a piece of what we have.

And what we have is this iconic outdoor landscape all around the city.

And so one of the questions that we ask ourselves a lot is, "What is that ethic, that wilderness ethic that we're imparting to people that are just moving here, to understand really what it means to be a Coloradan and how special it is to protect some of these resources.

JOHN HICKENLOOPER: There's a word called "topophilia", which most people have never heard.

But topophilia means "love of place".

And most people love where they are.

Not everybody, we move around a lot, but there is, for most people, a strong love of place.

And once you love a place, then you're gonna pay attention to the environmental circumstances and the consequences of your actions.

CHUCK LEAVELL: The most important actions now are about enhancing the future of Colorado s forests.

MOLLY PITTS: So as I look to the future, to the next 10, 15, 20 years, um, the spruce beetle will have come and gone, um, primarily because they've run out of food.

MOLLY PITTS: We ll also see a lot of the younger, smaller trees, since they're released, getting more nutrients and sunlight.

MOLLY PITTS: We're hoping that as we get more and more data, that that trend will continue.

That we'll continue to see the evidence that we're doing a really good job of protecting our next forest.

CHUCK LEAVELL: You know there's a wonderful quote from Ralph Waldo Emerson when he said, "In the woods, we return to reason and faith."

And you know some of our incredible veterans need some healing from time to time, and there's a lot of healing in these woods and in these waters.

CHUCK LEAVELL: I'm here in the mountains between Denver and Colorado Springs, where I've come to meet with a very special group of veterans at the Rainbow Falls Mountain Trout Club.

This club is one of Colorado's oldest trout fishing locations, with nine lakes and a meandering stream nestled in a private forest.

There's a saying that trout grow on trees.

That is, you need a healthy forest to provide the right habitat for the fish.

And not only is this the right place, but I've found the right teachers too.

CHUCK LEAVELL: And I'm here with my new friends Matt O'Neil, and Mitch Dziduch ... right?

MITCH DZIDUCH: Yes, sir.

O'Neil, and Mitch Dziduch ... right?

MITCH DZIDUCH: Yes, you did, Chuck.

CHUCK LEAVELL: I'm proud.

MITCH DZIDUCH: You're all over it, man.

CHUCK LEAVELL: First of all, let me just say thank you for your service, I mean that sincerely.

I think, Matt is still active?

MATT O'NEILL: Yes sir, I'm still active Army out of Fort Carson, Colorado.

CHUCK LEAVELL: and Mitch, you're retired?

MITCH DZIDUCH: I'm retired from 10th Special Forces Group, Fort Carson, Colorado.

CHUCK LEAVELL: And you're gonna try to make me a fly-fisherman, aren't you?

MATT O'NEILL: That's the hopes.

We're in the right spot, that's for sure.

CHUCK LEAVELL: Matt and Mitch are members of a veteran's organization called Project Healing Waters.

The group has a simple goal- to use the power of nature to help veterans recover from their wartime wounds.

MITCH DZIDUCH: I've been doing this since 2014.

A buddy of mine ...

I ran into him in the commissary, and he asked me if I was into fishing?

I said yeah; he knew I was a disabled vet.

I love Project Healing Waters.

They've done so much for me, they've calmed me, tremendously.

I love coming down and relaxing, on the rivers, and scenery like this; I mean this is beautiful.

If you cannot relax in an environment like this ...

I do not know where you can relax.

CHUCK LEAVELL: When I'm not around, Mitch has way better luck catching fish.

In fact, Project Healing Waters sponsors an annual Battle of the Boxwood on the South Platte where Mitch and others show off their skills with the rod.

Skills that I'm determined to master.

MATT O NEILL: So, imagine you're holding a coffee cup.

You've got your thumb up over the top.

And you're going to throw that coffee cup over your shoulder.

CHUCK LEAVELL: Right.

MATT O'NEILL: Now what we're going to do is we're going to watch that line unroll behind us.

As it gets pretty close to being fully extended, we're just going to gradually go forward and follow the line down.

MATT O'NEILL: Like I said, if you cast over that way.

Good.

Feel it unroll.

Nice.

Well done.

CHUCK LEAVELL: How long did it take you to get a good feel for this?

MATT O'NEILL: I don't know if I'm the greatest caster still, when I watch people like Mitch that do it effortlessly ... that was a big thing for me, trying to do things too strong and fighting the line.

Just relaxing ... MITCH DZIDUCH: Now if you did happen to get a strike, what I've always been taught is not to jerk.

You basically want to say, "Hail to the Queen."

Just lift that nice and easy.

CHUCK LEAVELL: I like that.

MITCH DZIDUCH: That's the way I've been taught.

CHUCK LEAVELL: Fly fishing isn't really about catching the fish.

It's about finding peace.

MATT O NEILL: Even days that you don't catch fish it's just peaceful to get out here.

My son and I have gone out, the reward of him catching his first fish a couple weeks ago was amazing.

Just the solitude, you're focused on something else.

You're not thinking about everything else just that, you know, is going on in life.

CHUCK LEAVELL: Today, all the trout stayed clear of my line.

But I caught something better - the spirit of Project Healing.

MITCH DZIDUCH: After a year of doing this, I was getting so much out of it, so much enjoyment, so much relaxation, I decided to become a volunteer.

So, I'm a participant and a volunteer.

I like working with these guys, helping them catch fish.

It really does a lot for me right here.

MUSIC CHUCK LEAVELL: Thanks for watching.

And I hope you ll join us on the next episode of America's Forests with me, Chuck Leavell.

In the meantime, enjoy the woods and enjoy the music.

Support for PBS provided by:

America's Forests with Chuck Leavell is a local public television program presented by RMPBS