Determined: Fighting Alzheimer's

Season 49 Episode 5 | 53m 28sVideo has Audio Description

Follow three women enrolled in a new study to try to prevent Alzheimer’s.

Follow three women at risk of developing Alzheimer’s as they join a groundbreaking study to try to prevent the disease – sharing their ups and downs, anxiously watching for symptoms, and hoping they can make a difference.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

National Corporate funding for NOVA is provided by Carlisle Companies and Viking Cruises. Major funding for NOVA is provided by the NOVA Science Trust and PBS viewers.

Determined: Fighting Alzheimer's

Season 49 Episode 5 | 53m 28sVideo has Audio Description

Follow three women at risk of developing Alzheimer’s as they join a groundbreaking study to try to prevent the disease – sharing their ups and downs, anxiously watching for symptoms, and hoping they can make a difference.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch NOVA

NOVA is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

NOVA Labs

NOVA Labs is a free digital platform that engages teens and lifelong learners in games and interactives that foster authentic scientific exploration. Participants take part in real-world investigations by visualizing, analyzing, and playing with the same data that scientists use.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship♪ ♪ KIMBERLY: I'm going to say more numbers.

After I say them, I want you to put them backward.

Two, eight, five, one, six.

Six, one, five, eight, two.

Four, one, six, four, three.

Three, four, six... One, four, two?

♪ ♪ Hi, Mama.

(laughing) BARB: I think I have probably a little greater than 50% chance of getting it.

I have lately thought, "You know, you got about another ten years of memory left before you hit your mom's stage."

♪ ♪ I absolutely am terrified of it.

♪ ♪ KIMBERLY: I'm going to read you a list of words.

I want you to tell me as many words as you can remember.

Okay.

All right.

Flute, dress, alarm, juice, office, mother, pond.

Flute, dress, juice, alarm, office, mother...

Draw on the hands at 20 minutes after 7:00.

KAREN: I knew it was too late for my mom.

But I have to think about my son.

Hopefully, if not in my lifetime, in his lifetime, they can find a cure.

It takes generations, sometimes, to find a cure.

♪ ♪ SIGRID: I'm noticing in my journey through memory that when you give a really long list, then things start to get really confused, and I can't track it anymore.

Mm-hmm.

SIGRID: I read that if you were a daughter of someone with Alzheimer's, that you had a much higher chance of having it.

My mother had passed away from Alzheimer's.

I had three daughters, and that's when they told me about the study.

And I said, "Oh, sign me up!"

NARRATOR: An estimated 50 million people worldwide live with Alzheimer's disease or other dementias.

Having a parent with Alzheimer's more than doubles a person's risk of getting it.

Now, some are joining a groundbreaking medical study to try to find out what, if anything, could make a difference for future generations.

"Determined: Fighting Alzheimer's," right now, on "NOVA."

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ STERLING JOHNSON: This study is about adult children of people who have Alzheimer's disease.

We bring our participants in in mid-life, and we follow them as they age.

We want to know who goes on to develop dementia and who doesn't.

We want to be able to prevent this disease.

In order to do that, we have to identify it as early as we possibly can.

We also want to know if there's a drug or a lifestyle intervention that will slow the rate of cognitive decline.

Ultimately, we want to prevent dementia.

So we call our study the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer's Prevention, or WRAP.

WRAP, to me, is super-groundbreaking, because when it was started, it was one of the first to actually look at the adult caregiver, um, the adult child.

♪ ♪ (birds chirping) MARK SAGER: My wife and I were sitting in the backyard, and it was a summer evening in Madison, and we were having a drink before supper.

I was commenting that at the time, there was almost no Alzheimer's disease research here on campus.

And my wife said, "You need to study someone like me."

(inhales) (voice trembling): And her mother had developed Alzheimer's disease.

(sniffs): And I said, "Well, it sounds like, you know, it's a good idea," and actually, it was a very good idea.

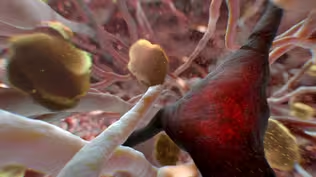

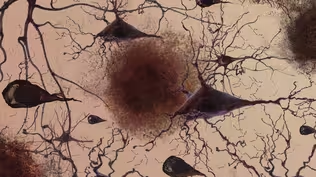

Alzheimer's disease is defined by two things, amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles.

These things show up in the brain in our 50s and 60s, and eventually, they become toxic to the cells that are vital for brain function.

After so long, symptoms of dementia develop.

KAREN: My mom didn't think it could happen to her.

She read, she was active.

And she didn't think it would hit her, and it did.

She couldn't escape.

♪ ♪ My mom always made things fun.

She would go outside, play kickball with me.

She even made housework fun.

Until I got smart enough and realized, "No, I shouldn't be enjoying this!"

(laughing) She always kept us laughing.

But I started noticing, she just didn't seem herself.

She wasn't reading as much.

She wasn't laughing as much.

And she had mentioned that she thought she was losing her memory.

Her sisters and her brother had Alzheimer's, and I was kind of worried that was going on.

And if it wasn't Alzheimer's, I wanted to find out what it was to get her treatment, to get her help.

And, uh... (crying): Unfortunately, it was Alzheimer's.

♪ ♪ And she would become angry when you would try to help her.

And I tried to explain, "I'm not trying to treat you like a child.

I'm just trying to help you."

Imagine seeing someone wither away to where they don't know when to go to the bathroom.

How to walk.

How to move their arms, their head.

It got to a point where I couldn't keep her at home.

I had to start giving it thought to her being placed in a nursing home.

It was the toughest decision I ever had to make in my life.

♪♪ ♪ My son was three when she was diagnosed.

XAVIER: She loved me.

Like, she would never get mad at me at all.

She'll get mad at other people.

But not me, for some reason.

We was like twins.

KAREN: Had my son in daycare, working full-time, now having to worry about her safety.

Stress was... You know, just, part of my life, everyday life.

Up until she died.

XAVIER: It doesn't feel the same without my grandma being alive.

The person who loved me the, really the, really the most, passed away.

KAREN: I want him to graduate from high school, go to college.

Find a career, have a family.

I want us to rekindle our relationship.

I missed a lot of time as he grew up taking care of my mother.

I always thought, "There'll be more time."

Always, "We'll do this later."

Xavier!

KAREN: We'll have the fun later.

And later turned into 12 years later.

♪ ♪ If by some chance you lose capacity when you're in this study, do you want to continue doing this study, or do you want to withdraw?

Yes, continue.

Okay, could you initial there?

And then we ask for a name of someone who can speak for you if that's the case-- if you lose capacity.

KAREN: I don't care what test it is.

I don't care if it's a lumbar puncture, a MRI, blood work.

I don't care, I'll do it.

Only part I don't like is the cognitive testing.

Chicken, orange, pond.

KAREN: That, although it's painless, it does make you feel stupid, and, uh, I just wonder why I'm able to roam around free after I take those tests.

♪ ♪ CYNTHIA CARLSSON: Take a breath and hold it.

(Sigrid inhales) Okay, take a breath again.

(inhales) And then hold it.

SIGRID: My mother was just such a very talented person.

Plus, she was also very bright.

But I can remember being at my mother's one time.

She held her head and she said, "Oh, I think I'm going crazy, I just think I'm going crazy!

I can't remember anything!"

And we said, "Oh, Mother!

We can't remember where our car keys are, either."

You know, "Nothing's wrong," we just sort of blew her off.

(sighs): I think even when you, you do understand intellectually... (sniffles): ...it's very hard to experience someone with Alzheimer's up front and close.

She followed me around like a, like a toddler, or a, a, like a dog.

(voice trembling): I remember turning around, and really just shouting at her, "Stop following me around!"

(crying) And I'm so sorry for that.

(sniffles) ♪ ♪ CARLSSON: You doing okay still?

SIGRID: I'm fine.

CARLSSON: If you're trying to diagnose someone at risk for Alzheimer's, you want to go back before they're ever having memory symptoms.

CARLSSON: Okay, the needle's out, you can lift your head and relax.

NURSE: Lift your head.

You feeling okay?

SIGRID: Yeah, and I don't have a headache yet.

Good!

There you go.

And I'll go get a warm blanket, okay?

BARBARA BENDLIN: At the very earliest stages, people actually can have normal cognitive function.

We're looking at a silent process.

So we're really trying to map out those early changes in fine detail, using sensitive methods.

CARLSSON: There are two main proteins that we focus in on.

So one is amyloid protein.

Amyloid that's in the spinal fluid gives us an idea about how much is in the brain.

And then I'll have you lie down here.

Watch your head so you don't hit the coil.

Right.

(MRI scanner whirring) JOHNSON: Traditionally, the way to diagnose Alzheimer's disease was with neuropathology examinations after a person has died.

Now, that's really still the way to get a definitive diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease.

But brain imaging is now a window into the living brain.

JOHNSON: Let's look at that hippocampus, Ron.

Here's the hippocampus right here.

So we're able to observe very subtle changes in the hippocampus, the structure that's very important in forming new memories.

This is really interesting, because this individual is only 64 years old and is cognitively normal.

But they happen to have a parent with Alzheimer's disease.

So the question that we're trying to address is whether this kind of profile, where you've got normal metabolism, but you're already seeing budding signs of Alzheimer's disease, will this person go on to get symptoms?

Or will they remain stable for their entire adulthood?

DAVID: What?

SIGRID: Did you find your glasses?

DAVID: They're the old-style glasses.

They are just someplace very, you know, like, out, laying somewhere.

I don't know what to do.

Other than, other than try and find them.

Oh, dear.

Dear, oh, dear.

DAVID: I guess I am slipping.

A lot of things I do forget.

Sigrid says I'm always having a fresh new experience every day, even though it, I may have actually done it some time recently.

(chuckles) I don't have the sense of being confused or in a fog.

It's just, I don't, uh, can't keep track of things as well.

When we started the study in 2001, it was just people who have a family history of Alzheimer's disease.

But we soon became aware that having that kind of a focused group may not be representative of the general population, and so we developed a control group.

NURSE: And... (scale beeps) Okay.

And you can bring your head forward... Up, nope, just head, there you go, just like that.

Now bring this down, and try not to crush you there.

Does that feel tight?

68.7 inches.

Five... Five-eight.

Just a hair under five-nine.

I know.

I used to be five-ten- and-a-half, so... Did you?

Yeah.

DAVID: Well, uh, we do the same tests that everybody else does in the program.

We have the blood test and, like, a three-hour cognitive inventory.

So they are doing everything, I think, that they're doing with the regular group with us.

I'm feeling like if I'm gonna have memory problems, then you're not gonna have my assistance, and you're going to be left with all this stuff behind.

Yup.

Of course, obviously, we gotta throw away stuff.

Would you say that louder?

We gotta throw away stuff, but I, I... Having saved it for ten years...

Ten years?

...to look at.

You have college, you have college course notes.

Yup.

SIGRID: Throw them out.

I want some peace.

♪ ♪ Put that one on top.

Good load.

Put the other one on top.

BARB: You like your maple and brown sugar, Dad says.

BARB: Take your warm blanket off you?

(Irene moaning lightly) I'm going to hold it up around her arms while you change her.

Just 'cause she gets so cold.

It's okay, Mama.

(Irene moaning) (Irene moaning) Here we go.

Down we go.

DOREN: If she made a little noise, they'd give her Ativan, knock her out, so she wouldn't make any noise.

And, uh, I just fought all, all seven months up there.

♪ Ay, ay, ay, ay ♪ ♪ Ay, ay, ay, ay ♪ ♪ My little señorita ♪ (chanting wordlessly) BARB: She's gonna get you singing.

(laughs) She's trying to copy you.

CRICKET: I know, she usually does.

BARB: She knows his voice.

He walks in the room and speaks, and she's listening.

Oh, there.

Oh, there... (babbling) BARB: I live five hours away from my parents.

I try to get up there as frequently as I can, at least every few weeks, um, but it's hard when you get a call that there's a crisis and you can't be there.

He would always stress, "Well, I can take care of her myself."

But we said, "No," I told him right out, I would not let her come home if he wouldn't agree to having help come into the home.

Ready to have a sip?

(whistles) SUE: Part of this disease is that eventually they will get so that they can't swallow.

That's why I'm concerned about how fast she's given things to drink.

Feeding her slow is okay.

CRICKET: I was giving her a drink of water one day, and she choked.

We all panicked.

And I know if I'm feeding my mom something, and she choked and didn't recover from it, I know my dad would hold it against me.

The girls, they all said, "Well, Dad, how are you gonna, "how are you going to take care of her?

"How are you going to take care of her?

How are you going change her?"

And I said, "Just let Dad do it.

I'll show you I can do it."

I guess I feel the same about her that I did back then.

♪ ♪ Well, we've had 59 years of very good marriage.

We worked hard together, she was always right by me, and... You just got to keep on loving her and taking care of her.

(Irene murmurs) You okay?

Hm?

All right.

I guess so.

(car signal beeping) KAREN: For the last several years of our marriage, I felt a strain.

In my mother's last six months of life, the one thing I always felt was, I was alone.

I would be there 23 hours, a day.

I'm trying to deal with my mom, trying to get my son to school... Whatever.

(alarm chirps) KAREN: ...raising a teenager, and trying to adapt life to meet my mother's needs.

When I think about the lack of support, there's a lot of hurt and a lot of anger.

(basketball bouncing) I do not like school at all.

It is stressful.

KAREN: My son can't go back to school because of his grades.

(chuckling) (sighs and sniffles) ♪ ♪ DIANE: I'm going to show you a sheet that has six figures on it, and I want you to study the figures so that you can remember as many of them as possible.

You'll have ten seconds to study the entire display.

♪ ♪ When I take it away, that's when you start drawing.

Now draw as many of the figures as you can.

Can't do it.

All right.

Well, that was fine.

I'd like to see whether you can remember more if I give you another chance.

That's all I could think of.

Try not to forget this display, because I may ask you about the figures again later.

Okay.

Okay.

DIANE: I'll present the display again for ten seconds.

Try to remember as many of the figures as you can this time, including the ones you remembered in your last attempt.

(stopwatch clicks) Now draw as many of the figures as you can.

(chuckling) I was going to really remember that one, but I don't.

Okay, that was fine.

When you took it, did you feel like you did better two years ago?

I mean, do you feel... Oh, I'm sure I did better... You did, so you feel like you're failing a little bit, too.

Absolutely, absolutely.

Absolutely.

I always feel badly about myself.

When I do this.

Yeah.

'Cause I think it's kinda startling to really have to face your memory gaps and what that means.

Yeah, it is.

It's hard to take-- it's hard to take.

Well, I guess my question... And I realized, I summed it up... My question to you is this, is, did you at any point really feel taken aback or shaken?

Today?

Yes.

No.

No, see?

I did, so, there's a message in that.

Yeah.

Right?

Yeah.

Well, I know.

I know that you're worried, I know.

So now, what you know about Alzheimer's?

I gotta ask you, you know I do.

WOMAN: Oh, my momma's getting a touch of some sort of dementia.

GREEN-HARRIS: Dementia is the loss of this cognitive function.

Thinking, remembering, reasoning.

It really is that broad-brush definition.

Alzheimer's disease, this is the umbrella for dementia.

If we were to have a spoke, Alzheimer's disease would be a spoke.

It is a type of dementia.

Alzheimer's disease, or dementia, can be in the brain for years and not show.

Does it affect us differently?

CELENA: Well, we're two times more likely with getting this disease, and being a woman, we're also two times more likely with getting Alzheimer's disease.

Have you ever thought about getting part of research?

Can I at least talk to you about it?

(laughs) So if I were to ask you to be a part of our research study, what would your, what would your thoughts be?

What would some of your challenges be?

I would, I would say, I probably wouldn't be.

MAN: You know, we, as African Americans, are skeptical about research.

GREEN-HARRIS: Mm-hmm.

We haven't had any past history of good fortune in research.

And we feel apprehensive about people experimenting on us.

GREEN-HARRIS: Yeah.

GREEN-HARRIS: Even though we know folks don't want to be involved, we know we have to be involved, because we're two times more likely to develop some kind of dementia in the Black community.

MAN: Yeah.

Why is that?

Why is that?

It has a lot to do with our health.

(inaudible) It has a lot to do with our social determinants of health.

Stress, and we're trying to, but you know what?

The biggest thing is the question mark, that's why we need you to be involved in our research study.

So we can find out.

So we can find out.

I don't think it was intentional, but there was just a lapse of recruitment of African Americans in the beginning of the study.

Over time, it obviously became recognizable that there was the absence of folks of color.

So in 2006, they started trying to recruit African Americans, but it was fairly unsuccessful.

And I think the original thought was that, "Oh, we just haven't asked."

But there was the misunderstanding of how to ask.

Oftentime, you have Caucasian investigators coming into Black communities and saying, "Okay, I'm here in my white coat, "I'm here as the white knight, I'm coming to save you, and I've got all these ideas."

And never asking the community for their ideas.

MAN: I've noticed in our community there's a lot of stigma.

And a lot of information that has been old information that people are continuing to recycle over and over again.

Is there any materials that we're able to actually have to be able to talk to these individuals?

'Cause there's not a lot of education that's going out there.

GREEN-HARRIS: We still have the issue around Tuskegee.

The level of offensiveness that occurred with Tuskegee has also continued to happen over the years.

And so that is also in the forefronts of our mind.

♪ ♪ DAVID DICK: For 40 years, the general public in Tuskegee and Macon County, Alabama, was unaware the federal government was experimenting with 430 local Black men who had contracted syphilis.

They were used as human guinea pigs to determine the effects of the disease.

28 men died as a result of the untreated syphilis.

When the program became public knowledge last year, it was halted.

But so far, a citizens' panel has been unable to force H.E.W.

to help those who survived.

I want to see the citizens of Macon County and Tuskegee who were utilized in this study receive adequate compensation.

GREEN-HARRIS: Any investigator that does not understand the impact of how communities of color have been unfairly treated when it comes to research, they're doing themselves a disservice.

We had to actually convince the community, and we had to say what made us different.

So what made us different?

We didn't just go out and say, "Hey, can you be a part of our research?"

We actually started by developing our community advisory board to talk about, how do we address this thing called Alzheimer's and dementia in the Black community so that we can build this new research model?

The question is: what do you do with all that data?

And how come we never see it after you get this information?

We curate this data and share it with people all over the world.

We're part of a consortium of, of other cohorts like the WRAP study.

But we share our data with any investigator throughout the world who has a question that we can answer.

All right, we have one more consent form.

We do have permission now to give you some more results about your memory testing.

So are you somebody who would want to know...

Yes.

...some more information if there was some cognitive changes or not?

Okay.

So how this is going to work is, Dr. Sager and the scientists will review your memory testing.

If they see anything, they'll give you an overview of the concerns.

SIGRID: When I failed to be able to reproduce these figures on my piece of paper, and couldn't do it three times and broke down and cried, I was convinced it had to be Alzheimer's.

This was the beginning, this was the beginning of, of the end.

And so when he called and said to me, um, "I don't see any signs of early Alzheimer's, "but are there other things in your life that might be causing this?"

And I said, "Well, "my 46-year-old daughter died of heart arrhythmia "very, you know, very suddenly and unexpectedly, and it was such a shock, and yes, I'm depressed."

I'm trying to get to her, the depression scores.

Yeah, here we are.

Depression and low mood, even anxiety and stress, those things affect memory.

Depressed mood can cause memory dysfunction to such a degree that it can fool some physicians into thinking it's Alzheimer's disease.

SIGRID: And I thought, "Okay, I gotta get depression off the table if I can."

And also, you know, up my game, so to speak, on exercise and things that I know might delay Alzheimer's.

TRAINER: Good, bend the elbows a little bit, just like you had it.

SIGRID: Bend the elbows a little bit.

TRAINER: There we go.

Good.

Bring them up.

Good.

TRAINER: Fine, chin up.

Three.

Nicely done!

Are these light for you?

I don't want to say that, because then you'll, you'll make it harder.

Yeah, I know.

(laughs) Right there.

Good!

Good!

Right there.

Perfect.

Right where the forearm and the bicep touch.

Good!

SIGRID: The thing that's going to make me the most determined is this scare of becoming the next in my family to come down with Alzheimer's.

♪ ♪ NEWS REPORTER (on TV): Reporting live from Milwaukee, Crystal Gantner, Fox 6 News.

Teachers are here, and again, everyone will be coming very shortly, because in just about 20 minutes, that's when that bell-ringing ceremony is scheduled... KAREN: Come on, people.

Move, move.

I better get my Boo-Boo to school.

Don't call me that.

What, Boo-Boo?

No.

Don't call me that.

KAREN: He's at that age, being 16, where, you know, they try to act all tough.

But here he's starting off at a new school.

He, I don't think, knows what to expect.

I don't know.

He wasn't really clueing me in this morning.

XAVIER: All right.

See you.

KAREN: All right.

I'll see you at 4:00.

You're my baby.

(calling): Bye, Boo-Boo!

I know you hear me.

(talking in background) WOMAN: Although the research is important, there's still reaching out to the caregivers.

Because when you go down, who helps her?

WOMAN: That's right.

GREEN-HARRIS: The caregiver is the great denominator, right?

And that's why we have the relationships with the folks around this table.

Let's start talking about what we're learning from that research.

We do know that lifestyle and behavior changes, eating modifications, we know that has some impact.

With my mom, her diet changed as her dementia progressed.

Has someone looked at that difference?

BENDLIN: That's a really good question, and it's part of the reason why we want to look at people who are healthier, as well, and may not have diet changes.

KAREN: Being part of this board is super-important for me.

It gives me a sense of purpose.

I'm not just, you know, being a test subject, but having a voice.

I believe that there will be an intervention.

There will also, at some point, be a cure.

And I often liken what will happen if we're not participating to what happened with things such as hypertension.

Hypertension was studied in, primarily, white males.

When an intervention for hypertension was initially found, it worked in white males.

We want to be sure that when there is something there, we have been in the numbers and we will definitely be able to benefit from whatever intervention, cure comes from this research.

OZIOMA OKONKWO: With advance in age, the amount of atrophy that you see in the hippocampus actually is minimal.

Whereas when you look at those individuals who do not meet the guidelines for being physically active, that is when you tend to see the most shrinkage in hippocampal volume over time.

SAGER: The data is really compelling.

If you remember, about 33% of the population are considered physically inactive.

And so, this is a huge reversible, you know, risk factor.

BENDLIN: Right, and so, what are the instructions?

OKONKWO: So for this, you put someone on a treadmill and have them walk or run until they are exhausted, you know, pretty much.

SAGER: It takes about six to eight minutes to do.

And it requires a blood pressure, a pulse, and a stopwatch.

That's it.

And that's it.

And two cones.

And some cones.

(all laughing) ♪ ♪ OKONKWO: This morning, we're going to be working you real hard to see how hard and how far you can get before you...

Pass out?

Well, hopefully not!

(laughing) During the exercise test, you'll be wearing a mask that's kind of a blue, rubbery mask.

SCHULTZ: And what that does is, when you breathe in air, all the air that you exhale will be captured and transmitted to a gas analyzer.

JEAN: Ten percent, three-and-a-half.

SCHULTZ: And that gives us a really good indication of overall physical fitness.

JEAN: 42!

Thank you!

SCHULTZ: Then we can use this data to relate it to some of your other measures that you've been collected in.

So we can relate physical fitness to cognition.

BARB: Whew!

Good job!

Five percent, three miles an hour.

OKONKWO: Physical inactivity is well known to be a modifiable risk factor for all kinds of cognitive changes in late life.

Okay, we're going to go up another hill.

Nice, even, big breaths.

Nice work.

OKONKWO: And the measurement of the highest oxygen inhalation that we were able to record has been shown to correlate with a slower rate of cognitive change in late life.

There you go!

Excellent work!

Whoo!

You killed that, that test.

You killed it.

(Sigrid chuckling) That, that is one of the best tests we've ever had here.

Absolutely, it was.

You killed it.

You're very kind.

You killed it.

You went as high up as one could possibly go.

♪ ♪ DAVID: You!

You are a frenzy of activity.

SIGRID: I think you really do need to think about exercising.

DAVID: Mm-hmm.

Yeah, that's true.

But the more time you exercise, and then you're tired at the end of it.

And so your, that... That moment of mental... SIGRID: I'm not tired.

I, I just exercised.

DAVID: I get tired at the end of it.

SIGRID: I know.

I just exercised, and what it does is, it boosts my energy.

What it does to me is, I want to take a nap.

(laughs) But maybe if you exercise more...

I want to move around mentally.

That's, I mean... No, you still have to physically move around.

You have to physically move around.

And circulate, you know, the blood throughout your whole body.

Studies are showing you shouldn't sit more than for, for, you know, 30 minutes or something, and you're supposed to get up and move around.

CHORUS: ♪ Jingle bells, jingle bells ♪ ♪ Jingle all the way ♪ ♪ Oh, what fun it is to ride ♪ ♪ In a one-horse open sleigh ♪ ♪ Hey ♪ ♪ Jingle bells, jingle bells ♪ ♪ Jingle all the way ♪ ♪ Oh, what fun it is to ride ♪ ♪ In a one-horse open sleigh ♪ (cheers and applause) GREEN-HARRIS: A diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease does not mean a death sentence.

You can still have quality of life!

And caregivers need support.

We're here to support that.

If I see somebody in need, I want to be there for 'em.

'Cause I would want somebody to be there for me.

♪ ♪ BARB: Come see Auntie Barb!

Come see Auntie Barb!

(gasps) Peeks!

Peeks!

BARB: We were trying to count great-grandchildren last night.

I ran out at 15.

No, Nana-Banana!

She's putting something on top of Gavin's head, and he's saying, "Look at my head."

(chuckles) Okay, there it is, Mama.

(child shrieking, laughing) Sippy.

DOREN: Hey, hey, hey... Quiet down a little bit.

Sue and I always make the appointment at the same time.

And then we go and have our brains tested.

That's what I call it.

We play games.

BARB: Okay, everybody smile.

Ada Potato, are you showing your biceps?

(all laughing) You got muscles there?

(laughing) Oooh!

Look at those pretty eyes!

BARB: Well, look at that!

Yeah!

She is in there after all.

You've pretty eyes, ain't you, honey?

Yeah.

Yeah.

Daddy's sweetheart, aren't ya?

(babbling) (wind blowing, birds twittering) ♪ ♪ (birds twittering) DOREN: I knew it was coming.

Yup, the last four days...

It was terrible.

(smacks lips) (speaks softly) Okay.

Dust to dust, ashes to ashes.

(weeping) It's okay.

(weeping) MAN: Would you like me to walk her out for you, Doren, or would you like to take Irene?

No, I'll carry her out.

I'll take her.

You let me know when you're ready.

Okay?

BARB: Monday morning, when we brought hospice in, you could see a grimace on her face.

So you could tell that she was having pain and she wasn't able to eat.

Yeah, look it.

Isn't it beautiful?

Oh, wow, that is very beautiful.

BARB: Oh, I've never seen that one.

DOREN: We both put on a little weight there.

BARB: Look at how curly her hair was.

DOREN: Ah, she, she was curly-headed.

(Barb chuckles) DOREN: That's a cutie.

BARB: I love her smile.

(laughing): That's you!

Oh, I know it.

1984.

CONGREGATION: ♪ And He walks ♪ ♪ With me and He talks with me ♪ ♪ And He tells me I am His own ♪ ♪ And the joy we share ♪ ♪ As we tarry there ♪ ♪ None other has ever known ♪ (song ends) (birds twittering) ADAM GONZALES: The setting is the annex.

When they say an "annex," it means a secret hiding place.

GIRL: That's Anne?

That is Anne.

That's Anne Frank.

Anne Frank had something in her that not a lot of people today have: a positive outlook on everybody and everything.

KAREN: He's never been a behavior issue.

Just, teachers are concerned because he wouldn't talk.

He's actually tried to answer questions in class.

Raise his hand a little bit more.

Say some things.

It's not... We can still go further.

But I can clearly see that he has been trying.

And that's a good start.

♪ ♪ She weighed 40 kilograms.

She's appearing older than the stated age of 73 years.

"The hippocampal sections of left and right "(C and R, respectively) are remarkable for attenuation of the fornix..." ♪ ♪ SIGRID: Oh, good, it's not too busy.

(exhaling) DAVID: Some people just get a buzz out of the whole thing, and I've never been a gym person.

(laughs) ♪ ♪ DAVID (breathing heavily): Well, you're still standing, so... SIGRID (breathing heavily): Well, yeah, I'm still standing.

How is your heart rate now?

125.

Good!

♪ ♪ (birds twittering) So this person was 61 when they started with WRAP.

They're 73 now.

Ton of amyloid.

The participant doesn't report any memory problems.

There may be some opportunities here to study what is it that makes a person steady over time in the presence of disease.

It's very interesting seeing how some of the things that people do every day are actually very critical.

Do you read newspapers?

Or play games?

Puzzles, checkers?

The findings have been compelling that the things that you do to keep your brain engaged actually do kind of help you push back against what one might have expected.

It will be curious to see how all of this pans out in the WRAP sample over time.

♪ ♪ Draw the lines as fast as you can.

Ready...

Begin.

♪ ♪ MAN: I'm wondering if any of you can touch on any evidence we have of the reversibility or at least the ability to slow the onset or progression.

Let's say we have a biomarker or we identify people at risk.

What can we do if they then, as a 55-year-old, improve those?

JOHNSON: We've seen that people who have certain healthy lifestyle patterns-- sleeping well, keeping cognitively and physically fit and active, modifiable things like hypertension, diabetes-- and it may be that if we can treat these things effectively, that may slow the progression of Alzheimer's pathology.

This is tremendously important, because it tells us that there may be an avenue of slowing down this disease in midlife, or in fact, preventing it entirely.

BENDLIN: In our studies, we've seen effects on the brain of a lot of different modifiable factors.

That said, you can do all those things right and you might still develop dementia.

DAVID: Let us get onto breakfast.

(Sigrid laughs) Bring me my breakfast!

Frozen kale from our garden.

(blender whirring) So today, as I understand it, they're going to inject...

It's not like, it's not like a dye, it's actually... She explained sort of like radiation?

Some form of, you know, radiation?

CARLSSON: What we're doing today is, Sigrid's coming in to be evaluated for participation in a clinical drug trial.

If she has any amyloid build-up in her brain, then she'll be eligible to receive this medicine that'll help clear out some of that amyloid.

And then we'll see if the medicine not only clears out the amyloid, but more importantly, if it helps protect her thinking abilities over time.

♪ ♪ WOMAN: It's a good reminder... Mm-hmm.

...that when you speak, not to... ...move your head.

And Sigrid, I am now injecting very slowly.

And Sandy has started the scanner, so we're starting the imaging right now.

SIGRID (voiceover): It's going to be physical evidence.

They are gonna sit down with me and they'll go over the results.

That will be very difficult.

This is one of the most important studies being done worldwide right now for Alzheimer's prevention.

I think it's going to be a critical point in time for us to see, if we get rid of amyloid, does it really help prevent Alzheimer's disease?

And if we get rid of the amyloid and it doesn't help thinking abilities, and doesn't help people, then that's going to give us a kickstart to go look in a different direction.

Hi!

Good to see you!

Hi, good to see you.

(speaks softly) CARLSSON: These are two separate people.

So this is one single individual at one point in time.

And this another individual.

And both of these people have Alzheimer's disease.

They've had memory symptoms for probably years.

They've had amyloid build-up in the brain for probably decades.

The warmer colors-- so yellow, oranges, and especially the reds-- those are the areas where there's some amyloid build-up.

Now, these two people are both healthy older adults.

This person has some amyloid build-up, though.

You can see that there are some areas that have some red.

Some warmer colors.

But they don't have any memory problems.

And they do not have Alzheimer's disease.

So, at this point, again, you are in this category.

SIGRID: You're kidding!

CARLSSON: No, I'm not.

Am I ever happy.

(laughing): We can go out for fish tonight and drink double Manhattans!

All right, but you'll miss all the fun.

Oh!

That is huge.

Huge!

Huge!

Sigrid is rejected.

Yeah.

Sigrid is rejected!

Huge.

Yes.

Very good.

Good to see you.

Enjoyed it.

Okay.

Yes.

Good news.

Enjoyed it.

Yeah.

Enjoyed it.

(laughing) Something to enjoy.

CARLSSON: That's right.

All right.

You take care.

I'll send Ben back in.

GLORIA GAYNOR: ♪ I could never live without you by my side ♪ Give me a kiss.

♪ But then I spent so many nights ♪ Good job, Sigrid!

Who knows what's lurking in my brain?

I know!

♪ But now you're back ♪ ♪ From outer space ♪ ♪ I just walked in to find you here ♪ ♪ With that sad look upon your face ♪ ♪ I should have changed that stupid lock ♪ ♪ I should have made you leave your key ♪ ♪ If I'd have known for just one second ♪ ♪ You'd be back to bother me ♪ Well, I guess the question is, where's the car?

(laughing): Yeah.

You sure you've got the ticket?

I've missed ya.

Thought about you lots.

Oh?

Think about calling you at 5:30 in the morning.

Well, I'm probably laying there awake.

And then I figure, "I think he's sleeping."

No.

WOMAN: One, two, three.

SUE: Irene's Sunbeams.

CRICKET: Thanks.

(laughing) BARB: Whoo!

Keep going, right?

Speed up?

(car horn honks) GIRL: Hi, Grandpa!

DOREN: We got quite a family.

(shrieking, laughing) ("Pomp and Circumstance" playing) (people talking in background) (cheering, whistling) All right.

Now it's time.

The NOVA, NOVA Tech graduates!

(cheers and applause) Keanu Avery.

(cheers and applause) Kevin McCall!

(cheers and applause) And our salutatorian, number two in the class, Xavier McElwee Lloyd!

(cheers and applause) (cheering and yelling in background) (people talking in background) I'm so very proud of you.

I love you.

KAREN: He's my Boo-Boo.

He's my Boo-Boo.

He's my Boo-Boo.

I'm a man.

I'm a man.

I ain't no Boo-Boo.

Mama, I made it.

Yes, you made it.

(cheers and applause) If it hits my mom, I just want to have that cure that I could just give it to her.

I'm actually glad that she's trying to help people with Alzheimer's.

I'm proud of it.

♪ ♪ To think that this disease was first described in 1906 and we didn't even have a diagnostic criteria till 1984.

Like, how to actually say that someone has Alzheimer's took almost 100 years.

And then to think of all we've learned, this is quantum leaps.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ANNOUNCER: To order this program on DVD, visit ShopPBS or call 1-800-PLAY-PBS.

Episodes of "NOVA" are available with Passport.

"NOVA" is also available on Amazon Prime Video.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪

Depression Can Affect Memory—and Mirror Signs of Alzheimer's

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S49 Ep5 | 1m 57s | Exercise may help depression patients regain memory. (1m 57s)

Determined: Fighting Alzheimer's Preview

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S49 Ep5 | 28s | Follow three women enrolled in a new study to try to prevent Alzheimer’s. (28s)

How an Alzheimer’s study reached Black communities

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S49 Ep5 | 2m 32s | Getting Black individuals involved in a study requires more than just asking them. (2m 32s)

Try Passing this Alzheimer's Screening Test

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S49 Ep5 | 2m 54s | You have 10 seconds to memorize six shapes. (2m 54s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- Science and Nature

Capturing the splendor of the natural world, from the African plains to the Antarctic ice.

Support for PBS provided by:

National Corporate funding for NOVA is provided by Carlisle Companies and Viking Cruises. Major funding for NOVA is provided by the NOVA Science Trust and PBS viewers.