Human Nature

Season 47 Episode 11 | 1h 33m 41sVideo has Closed Captions

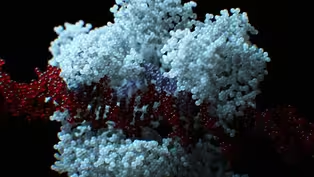

We can now edit the human genome with a tool called CRISPR. But how far should we go?

With an extraordinary new technology called CRISPR, we can now edit DNA—including human DNA. But how far should we go? Gene-editing promises to eliminate certain genetic disorders like sickle cell disease. But the applications quickly raise ethical questions. Is it wrong to engineer soldiers to feel no pain, or to resurrect an extinct species?

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Additional funding for "Human Nature" is provided by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. Additional production support is provided by Sandbox Films, a Simons Foundation initiative. Major funding for NOVA...

Human Nature

Season 47 Episode 11 | 1h 33m 41sVideo has Closed Captions

With an extraordinary new technology called CRISPR, we can now edit DNA—including human DNA. But how far should we go? Gene-editing promises to eliminate certain genetic disorders like sickle cell disease. But the applications quickly raise ethical questions. Is it wrong to engineer soldiers to feel no pain, or to resurrect an extinct species?

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch NOVA

NOVA is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

NOVA Labs

NOVA Labs is a free digital platform that engages teens and lifelong learners in games and interactives that foster authentic scientific exploration. Participants take part in real-world investigations by visualizing, analyzing, and playing with the same data that scientists use.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ FYODOR URNOV: Mother Nature gave us something that's richer than our imagination.

FRANCISCO MOJICA: We saw a very peculiar pattern.

Never seen anything like this before.

ANTONIO REGALADO: I remember him saying, "Remember this word: CRISPR."

JENNIFER DOUDNA: We've never had the ability to change the fundamental chemical nature of who we are, and now we do.

And what do we do with that?

♪ ♪ DOLORES SANCHEZ: David's doctor told me, "Just hold on.

There's something coming."

RODOLPHE BARRANGOU: You can actually use CRISPR to change DNA.

You can actually do it.

GEORGE DALEY: We could engineer a single gene that could potentially make us all more muscular.

But should we make that universally available?

VLADIMIR PUTIN (speaking Russian): ♪ ♪ MATT PORTEUS: Should we really be manipulating the heredity of future generations given our lack of knowledge about so many things?

PALMER WEISS: I don't know where you draw the line between not having albinism and deciding your kid needs to be an extra foot taller so they can be a good oarsman and go to Yale-- where is that line?

Who's gonna draw that?

MAN: Anything that will stop my child from suffering I'm for.

REGALADO: You know, draw this ethical line wherever you want, but don't draw it in front of my disease.

♪ ♪ PREACHER: What does this mean for this science, where we have the capacity to edit in some things that we think are important?

Are we playing God?

ALTO CHARO: You don't realize it's disruptive until you look backward.

Often you don't realize that you're in the middle of a revolution until after the revolution has occurred.

♪ ♪ ANNOUNCER: Major funding for NOVA is provided(applause)llowing: ROBERT SINSHEIMER: Dr. Bonner, fellow prophets, and... (audience laughter) Ladies and gentlemen...

This summer, I traveled through northern Arizona and southern Utah.

In this land, the rivers have carved great gorges, and on the sheer cliffs of these gorges, one can read a billion years of the history of the Earth.

On that immense scale, a foot represents the passage of perhaps 100,000 years; all of man's recorded history took place as an inch was deposited; all of organized science, a millimeter; all we know of genetics, a few tens of microns.

♪ ♪ The dramatic advances of the past few decades have led to the discovery of DNA and to the decipherment of the universal hereditary code, the age-old language of the living cell.

And with this understanding will come the control of processes that have known only the mindless discipline of natural selection for two billion years.

And now the impact of science will strike straight home, for the biological world includes us.

♪ ♪ We will surely come to the time when man will have the power to alter, specifically and consciously, his very genes.

This will be a new event in the universe.

The prospect is, to me, awesome in its potential for deliverance or equally for disaster.

(indistinct chatter) There we go, much better.

NURSE: You want to squeeze my hand?

Relax your shoulders.

Relax your toes.

DAVID SANCHEZ: Being in the hospital isn't scary to me.

Having a certain new problem isn't scary to me anymore, 'cause it's happened so many times.

I don't know, my blood just does not like me very much, I guess.

Your red cells are supposed to be round and have oxygen in them.

Mine are half-moon-shaped, sickle-shaped, which is why it's called sickle cell, so I don't get the same amount of oxygen.

(laughs softly) NURSE: I always say, like, oil change.

You know, you drain the dirty out and then put a clean in.

Yeah, so he just needs a tune-up every four to six weeks, yeah, uh-huh, yeah-- okay?

Okay.

Put this on.

Take deep breath and hold.

Mm.

Okay.

You okay, David?

Mm-hmm.

He used to tell me, "Don't cry, Nonna.

Why are you crying?"

(inhales): I said, you know... "Love you, baby."

He goes, "Don't worry about it."

He says, "If I lose my life," he goes, "You'll see me again."

And I thought, "This child has more strength and faith than I do."

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ PORTEUS: It's often called the first molecular disease.

It's caused by a single change in the DNA sequence.

It's the letter A changed to a letter T. INTERVIEWER: That's it?

PORTEUS: That's it.

TSHAKA CUNNINGHAM: And that mutation causes a kink in the protein that prevents it from folding properly.

If your folding structure of a protein is disrupted, now that protein can't function.

It causes the red blood cell to really collapse.

PORTEUS: It becomes very stiff and it can't squeeze through, and you're not able to get red blood cells to the tissues where they can deliver oxygen, and if you block the ability of oxygen to get to those tissues, those tissues won't work well and they'll get damaged.

(indistinct chatter) PORTEUS: In Africa, the life expectancy for somebody with sickle cell disease is on the order of five to eight years of age.

In the U.S., it's the early to mid-40s.

INTERVIEWER: What do you say to a kid that their life is gonna be... We avoid it-- we avoid that...

It's not a, it's... Really?

It's not a conversation we're good at having.

Makes me very nervous.

♪ ♪ David can go from crazy teenager, joking, jumping around, to a fetal position on his knees.

DAVID SANCHEZ: It's like... pulsing.

"This hurts!"

"You're having a sickle cell crisis!"

Look, I can have, like, a little pain crisis where it really doesn't count, and then I can have something really bad, but I'm not just gonna not play basketball.

You can't just not play basketball.

This is David's old red blood cells.

We're gonna save for research.

DOLORES SANCHEZ: How do you sing it?

CHILD: ♪ Rain, rain, go away, come again... ♪ CUNNINGHAM: It's a genetic disorder, so in order to cure a genetic disorder, you literally have to go in and fix the gene.

We just didn't have the tools to make that single-letter change in a precise fashion.

INTERVIEWER: Even one letter?

Especially one letter.

REPORTER: Deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA for short, is the material that's the basis of life.

Each living thing has its unique DNA that determines what that living thing will be: plant or animal, man or muskrat.

♪ ♪ PAUL BERG: If we understood the structure of genes, the structure of chromosomes, and how genes work, then we might better be able to understand and treat genetic diseases which occur in humans.

CHARO: The work that Paul Berg did, that was probably the beginning.

This dream of gene therapy was born out of those 1970s experiments, and we were still very far away from it, but you'll see people talking about that hope right away.

REPORTER: The hope is that the isolation of the gene will lead to treatment of people with muscular dystrophy.

REPORTER 2: Scientists are working on genetic cures for diseases such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's.

MAN: A, T, A, G, C... HANK GREELY: The idea behind gene therapy is really simple: add in a copy of the gene that works.

Then they'll make the protein that works, and then they won't be sick anymore.

But the devil, as is often the case, is in the details.

WAYNE MILLER: Right now, we have the ability to identify the gene, to isolate it, but the ability to put it where we want it is still a long ways away.

BERNARD D. DAVIS: If you put a gene into a cell, you cannot tell exactly where that gene is going to enter the cell's chromosome.

URNOV: Conventional gene therapy is an essentially random process.

So imagine taking this century-long narrative, which is human DNA, which is a very, very long text, and taking one paragraph and just sticking it somewhere random.

The change you are creating is not a controlled one.

REPORTER (speaking French): URNOV: There was a clinical trial that was done in France.

This was for really sick children-- I want to be clear.

This was for children who would have died otherwise.

Four of these children developed cancer.

One of them died.

The gene went into the wrong place.

Because it's a random process, and, by chance, it went into the wrong place, and that random event caused cancer.

♪ ♪ DAVID BALTIMORE: You know, you always think that what you know is gonna get a little better and a little better and a little better, and soon be there, and what we knew how to do wasn't getting a whole lot better.

It was getting a little bit better.

The technology was just too clumsy to actually use it with human beings.

It became very, very clear to us that we are at the foot of a very tall mountain and we may not even have the right mountaineering gear.

♪ ♪ I worked at this company called Sangamo Biosciences.

We decided to figure out a way to change human genes in a precise fashion.

You know, this would be like word processors for your DNA.

♪ ♪ This will get technical, but good technical.

DNA breaks all the time.

You go get a dental X-ray.

The technician points this thing at your face... (imitates X-ray): And the X-rays actually hit your DNA, and they physically create a break, so the familiar double helix of DNA physically goes (imitates breaking).

The good news is, the cell has its own machine to fixing breaks.

♪ ♪ Inside our cells, there are two identical DNA molecules lying side by side, literally side by side.

If one is broken, it can say to its sister-- and that, in fact, is the technical term, the sister-- "Hey, sis, I'm sorry.

I've had a break.

I'm wondering if I can copy the missing genetic information."

And the sister goes, "Yeah."

Done.

"Chromosome broken "awaits sounds of strands pairing, preserving life's thread."

There's really, there is really a haiku about homology-directed repair.

(laughter in background) Why is that useful?

So it's useful because if you can cut a gene inside a cell, so if you can create a break at a place of interest, then you can change that gene.

You fool the cell, give it a separate piece of DNA that you have made, a piece of DNA which is identical to the chromosome that you are cutting except for the change that you wish to make.

And Mother Nature will not know she's being fooled.

She will repair the break using this piece of DNA you provided as a template, and so whatever change you brought in will then go into the chromosome.

FENG ZHANG: You can think of it like a cursor in Microsoft Word.

In Word, if you have a document where you edit, first you have to place the cursor there.

In DNA, wherever you make a cut is the equivalent of a cursor in this word processor of the genome.

That's where you can type in a new word.

(keyboard clacking) DOUDNA: So if you wanted to use that capability to "engineer the genome," the challenge was to introduce breaks in the DNA at places where you wanted to, to alter the code.

URNOV: How were we gonna do that?

(slicing sound) We need something that cuts only one gene out of the, you know, 25,000 that we have.

BALTIMORE: There were just such serious blocks in the way.

So it looked like it was gonna be a long road.

And that's what changed.

And that came sort of overnight.

♪ ♪ DOLORES SANCHEZ: David's doctor told me, "Just hold on-- there's something coming."

REGALADO: When I first heard about it, I was at a conference in New York, and it was a very strange conference of, of futurists.

It was put on by a Russian guy whose ambition is to download his brain and become an android who lives forever.

In this future, people will be young, beautiful.

They will have multiple bodies, not only just one.

REGALADO: But they had a lot of good people there, including an important geneticist from Harvard, George Church.

And I remember him saying, "Remember this word: CRISPR," C-R-I-S-P-R. CHURCH: It's, like, you know, in "The Graduate," plastics.

Remember the word CRISPR.

This is going to allow human genome engineering on a unprecedented scale.

♪ ♪ INTERVIEWER: How old is CRISPR?

Oh, in terms of millions of years?

Yeah.

Oh, I mean...

Probably... billions.

♪ ♪ MOJICA: When you are a student, you think everything is known.

But there are places where no one else looked.

(birds and insects chirping) The organism I was working with is called Haloferax mediterranei.

This microorganism is very peculiar.

They only live in environments where the salinity is about tenfold that of the seawater.

These tiny organisms are...

I would say, even, so clever, yeah?

Clever because of the evolution, of course.

♪ ♪ JILL BANFIELD: Well, I'll tell you the story that I know.

Microbial genome sequencing started sometime in the 1990s.

INTERVIEWER: What does that mean?

See, okay, so, unraveling the DNA code of organisms of life is a relatively recent part of biology, and in the late 1990s, people started to turn their attention to the sequencing of microbial genomes.

They're amazingly highly evolved entities that just chose a different way of surviving in the world than the cells that became us.

(Mojica reciting letters faintly in Spanish) (Mojica reading letters in Spanish) MOJICA: We saw a very peculiar pattern.

These very short fragments of DNA.

They repeated many times.

And they were regularly interspaced.

Eventually, we realized these peculiar sequences, they were present in many different microorganisms.

But they didn't have really any name.

CRISPR came to my mind just thinking about the, the main features.

Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats.

URNOV: There really wasn't much precedent for anything like this in the DNA of living things, and when you see something unusual, you automatically assume that it's interesting.

That's just how science works.

BANFIELD: CRISPR is actually clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeats, and so, it's actually named for the repeats.

But what was really interesting were these sequences in between that were completely enigmatic.

MOJICA: Spacers.

BANFIELD: And each spacer was different.

♪ ♪ Never seen anything like this before.

Where the hell come these sequences from?

(Rachmaninoff's Piano Concerto No.

3, third movement plays) ♪ ♪ REGALADO: I have my own way of kind of telling the story in short form, is, I show this article from 2007, right?

Five years before anybody was talking about CRISPR, and it's this headline from a yogurt company saying, "Holy grail is discovered."

(concerto continues) And what was this yogurt company's holy grail?

It was CRISPR.

It was CRISPR.

INTERVIEWER: When did you get your CRISPR license plate?

BARRANGOU: The first one I got back in the days in Wisconsin, and when I first moved to North Carolina... (car alarm chirps) It was one of the first things I did, was to make sure I still had my CRISPR rights with my CRISPR-mobile.

(concerto continues) People were, like, "Have you heard about this CRISPR thing?"

And I'm, like, "Dude, like, "I've heard of this CRISPR thing for ten years.

Like, what the hell are you talking about?"

(concerto continues) BANFIELD: Danisco is a company that sells microbes to people who want to make food.

A lot of foods are produced using bacteria, and... Yogurt, for example.

Rodolphe was trying to work out how to deal with the problem of his bacterial cultures suddenly dying because of viral infections.

URNOV: Most people don't wake up in the morning and think about how bacteria defend themselves against viruses.

It's just not on their, on their, on the sort of front and center in people's agenda, but it should be.

♪ ♪ BARRANGOU: Viruses are very simple lean machines.

They have one job to do: look for a host, take the host over, and multiply, that's it.

LUCIANO MARRAFFINI: The virus will attach to the surface, and then it will inject its genetic material.

It hijacks the cell and use the cell just as a factory of new viruses.

And then it's over.

It's over for the cell.

BARRANGOU: This is when people call companies like Danisco and say, "You sold us a culture that's not working.

We want our money back."

But there's a small subset of the population that survives the viral attack.

We don't know why they make it, but they make it.

They become resistant.

At that time, we still don't know what CRISPR is and what it does, so there's no assumption that CRISPR is involved.

Then what we do is, we take the survivor that made it, and then we check its DNA.

The DNA sequence had changed.

♪ ♪ MOJICA: There are new spacers that were not present before, and those spacers are identical to sequences from the virus that infect bacteria.

BANFIELD: And now it's immune.

URNOV: So now scientists have a clue, and, you know, at this point, of course, you've sort of put your Sherlock Holmes hat on, you take in your virtual pipe, and you go, "What are these clues telling us?"

BARRANGOU: We do the experiment five different times.

And consistently, the bacteria acquired a spacer that contains a sequence from the virus and became resistant.

So what if I take it away?

You lose the resistance.

BANFIELD: Without that little piece of DNA, the microbial cell, the bacterial cell, will die, and if it had it, it would survive.

Oh, that was, like, that was, like, "We got it."

CRISPR is an immune system.

BANFIELD: What an idea: a piece of the genome of your predator now stuck in your genome so you can recognize it in the future.

Bacteria have memory.

They are able to remember invaders, recognize them, and kill them.

That was really fantastic.

BARRANGOU: At the time, you know, it's useful in manufacturing cultures that are resistant to viruses.

It's extremely valuable to Danisco.

You know, but...

But we don't know what the future holds.

(laughs): We have no idea how useful or not this technology is gonna be or pan out in the end.

(indistinct chatter) DOUDNA: I think I first heard about it when I had coffee with Jill Banfield, my colleague here at Berkeley, at the Free Speech Movement Café, classic Berkeley café.

One thing they'll write on my tombstone was, "Told Jennifer Doudna about CRISPR-Cas."

(laughs): Like, that will be the sum of my life.

♪ ♪ DOUDNA: I love things that not a lot of people are paying attention to, which certainly CRISPR was in its early days, not anymore, but, but, you know, in the early days, it was like that.

But then you always ask yourself, "Huh, is everybody else just a lot smarter than me "and they've figured out that this is a, you know, a dead path and..." (laughs) So we've got the antibody tethered to Cas9.

It's finding the T cell-specific antigen.

DOUDNA (voiceover): We're biochemists in the lab.

We study the way molecules work.

We try to isolate them from all of the other pieces and parts of the cell.

We love to ask, "Well, what are the essential parts of this little machine?"

In nature, what CRISPR systems are doing is, they're giving bacteria immunity to viruses, so they're protecting them from viruses.

♪ ♪ URNOV: When an invader shows up, the bacterium has a way to store a small bit of the invader's DNA in its own DNA.

When the invader comes back, the bacterium makes a copy, like a little "Most Wanted" poster of that spacer, and gives it to the marvelous machine at the heart of CRISPR, this extraordinary protein that we call Cas9.

Cas9 is truly wondrous.

When Cas9 polices the intercellular neighborhood for invasions, it literally carries a copy of that "Most Wanted" poster with it.

Asking everyone that comes in, "Excuse me, do you contain an exact match "to this little 'Most Wanted' poster that I'm carrying?

Yes?

Then I'll cut you."

(slicing sound) DOUDNA: The thing about Cas9 that struck me at the time was that, you know, fundamentally, this thing was a programmable protein that finds and cuts DNA.

As a tool, right, you could immediately see a lot of uses for something like that.

I will never forget reading the last paragraph of Jennifer Doudna's and Emmanuelle Charpentier's deservedly-- "immortal" is a strong word, so I'm gonna use it carefully-- immortal science paper in which they describe that Cas9 can be directed.

♪ ♪ Cas9 cuts DNA based on an instruction that it carries, and that instruction is a molecule of RNA that matches perfectly the DNA of the invader.

DOUDNA: RNA, I think about it as DNA's chemical cousin.

Like DNA, it has four letters, and they can form pairs with matching letters in DNA.

The letters in the RNA allow Cas9 to find a unique DNA sequence.

Bacteria were programming this thing all the time with different viral sequences, and then using it to find and cut and destroy those viruses.

But because it's using these little RNA molecules, those can easily be exchanged.

RNA molecules are trivial to make in a molecular biology lab or order from a company.

And I can cut any DNA I want just by changing this, this little piece of RNA.

(typing) It was clearly a useful tool, and I, initially, I was thinking about it that way, right?

'Cause, you know, again, I'm a biochemist, right?

I was thinking about it as a tool.

I was thinking about all the cool experiments you could now do with this tool, right?

I was thinking about that.

I wasn't thinking about... Oh, my gosh, I mean, this is a tool that, you know, it fundamentally allows us to change our relationship with nature.

It actually allows us to change human evolution if we want to.

Right?

It's that, it's that profound.

♪ ♪ MAN: In my left hand here, I have purified Cas9 nuclease, and in my right hand here, I have a guide RNA, and so CRISPR essentially is the combination of these two ingredients.

It's actually millions of Cas9 molecules, and this is millions of RNA molecules.

I have to say, it didn't immediately hit me, until I started seeing the data, that this could be an extraordinary transformation.

You know, it was real.

BARRANGOU: You can actually use CRISPR in humans to change DNA.

You can actually do it.

URNOV: Here's a copy of a human gene.

You give it to a Cas9 and put it inside human cells.

It runs away, finds that DNA, and cuts it.

PORTEUS: Before CRISPR, we were getting one to two percent correction.

We're now up to 50% to 80% of the cells.

This could really work.

This could really cure a patient.

DAVID SANCHEZ: I think it's gonna help a lot of people, not just people with sickle cell, 'cause I know they're working on it for other things.

And I know so many other people that have, that have things like this, like, like my friend, he... uh, had leukemia.

He actually didn't make it out of the hospital.

If he had it just a little bit later, of course, he probably could have been cured of that, 'cause that's what they're working on.

(mouse clicks) (mouse clicks) EMMANUELLE CHARPENTIER: CRISPR has, really, the ability to recognize and to target any piece of DNA in any type of cell and organism.

It's really a universal tool.

It's often described as a kind of Swiss Army knife.

♪ ♪ MICHAEL DABROWSKI: We have thousands of customers who are working with CRISPR in a wide variety of organisms, pretty much any organism you can think of, from butterflies to dogs to horses to wheat to corn.

We have a design tool online.

You can specify a gene that you're looking to knock out.

You can specify the types of edit that you're looking to do.

You swipe your credit card, and a few days later, a couple of tubes of all the materials that you need show up at your door.

Obviously, we like to validate the, the researchers' authenticity and credibility with regard to their institution.

INTERVIEWER: Meaning you're not just shipping it off?

Correct, we don't ship to just anyone.

That's correct.

♪ ♪ GREELY: The analogy I like is automobiles.

There were cars before there were Model Ts, but they were expensive and they broke down all the time.

Ford comes out with the Model T, and, suddenly, it's cheap and it's reliable.

Pretty soon, everybody's got a car.

(metallic clanking) ♪ ♪ (choir singing with orchestra) ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ GREELY: CRISPR gives us the chance to make precise, targeted changes in the DNA of any living organism.

It's a power to change the biosphere.

That's what makes CRISPR revolutionary.

♪ ♪ (choir and orchestra continue) ♪ ♪ (music ends) INTERVIEWER: Can you just sort of describe where we are right now?

Oh, here?

Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Oh, so here is the, um... eGenesis garage.

This is our lab space.

It's literally the basement.

I feel it's a humble start for us where we embark on a very exciting journey.

♪ ♪ JORGE PIEDRAHITA: The field is called xenotransplantation, transplantation of an organ from one species to the next.

These things have actually been tried a lot, and some of them are pretty weird.

Like, people were, were, you know, in the early 1800s, that kind of stuff, they were trying to transplant monkey testes into men to make them more virile.

So, so, you know, conceptually, people have been trying this for a long time, but scientifically, this field is probably about 20 years old.

Whether we like to believe or not, we are very similar to the pig.

This pig, this pig, this pig, all the organs in these pigs have been modified very, very slightly.

CHURCH: They tried it 20 years ago.

Novartis had had a billion-dollar investment in it, sort of gracefully, uh, retreated.

(pigs snorting) CHURCH: They, they just didn't have the technology.

Without the CRISPRs... can't do it.

CHURCH: Luhan Yang and her team, they started as a ragtag team of scientists in my academic lab, and then they went to a ragtag team in the basement of, of a startup incubator.

Nice to meet you-- hey.

(chuckles) Happy Halloween.

(laughter) You know, I dressed up today, you know?

Can you see anything?

Kind of-- something, not everything.

(laughs) So this is Yinan, Yinan is quite creative.

Probably more creative than me.

YINAN KAN: When I first heard the story, I thought, it is sci-fi, you know?

We're going to, we're going to make a pig that doesn't speak human language, but because they can donate organs for the, for the patient and save the world from, like, organ shortage.

I mean, it really takes a lot.

♪ ♪ YANG: As you can imagine, if you put the organ from the pig into the human, there's a rejection.

We can really exercise the power of CRISPR to engineer immunocompatibility by knocking out genes and knocking in genes.

♪ ♪ KAN: If you compare the pig genome to an encyclopedia of this thick, so what CRISPR does is, it can find, like, a specific, a specific word in the encyclopedia and delete that word.

But instead of, like, deleting a few words, we have to change paragraphs after paragraph.

YANG: Right now, the conventional practice is doing one or two genes.

And the record before us is five.

(chuckling) YANG: We did 62 genes in single step.

(phone camera clicks) CHURCH: We have a revolution going on that we've never had a revolution like.

The closest we've come is, is maybe the internet and computer revolution.

And that took us kind of unaware.

We do a lot of iteration of the pig production.

INTERVIEWER: How are the pigs coming along?

They are coming.

(chuckles) So, uh... We are expecting some pigs in, in a few weeks.

We're so excited, we even named the pig.

The first one is Laika.

It's the name of the Soviet dog which orbit the Earth first.

♪ ♪ We want to symbolize it as an animal which can lead us to a new era of science.

(engine roaring) WOMAN (speaking Russian): (cheers and applause) PUTIN (speaking Russian): ♪ ♪ REPORTER: This is Aldous Huxley, a man haunted by a vision of hell on Earth.

Mr. Huxley 27 years ago wrote "Brave New World."

Today, Mr. Huxley says that his fictional world of horror is probably just around the corner for all of us.

♪ ♪ DALEY: I first read "Brave New World" in a literature class in high school, and, yeah, it was startling, and, yeah, it was provocative.

Um...

But I reread it recently, and I was startled by how a book written in 1932 could have the foresight to predict in vitro fertilization.

♪ ♪ (crying) DALEY: Now, of course, it went beyond it.

It told a story where human beings were literally manufactured to play specific roles in society.

It was so sobering to me because CRISPR makes that original worry about engineering human heredity actually feasible.

(device clicks) ♪ ♪ HUXLEY: We mustn't be caught by surprise by our own advancing technology.

This has happened again and again in history, where technology has advanced and this changes social conditions, and suddenly, people have found themselves in a situation which they didn't foresee and doing all sorts of things they didn't really want to do.

♪ ♪ URNOV: There is no question in my mind that as this field advances, people will be able to order a change in their genetic makeup to create an outcome of interest to them: in their metabolism, in their appearance; in principle, potentially, in who they are as people, personality changes.

And, again, we have to be delicate to not cross into science fiction territory.

DALEY: We know that we could engineer a single gene, myostatin, in a way that could potentially make us all more muscular, but should we make that universally available?

They discovered that there are people who can go by on four hours of sleep.

What would I give for that mutation?

One gene, one change, four hours of sleep, no problem.

So... should this be, I don't know, a job requirement for air traffic controllers?

♪ ♪ Do I want the world to go there?

♪ ♪ There are people who feel no pain.

This was discovered by studying a 14-year-old boy in Pakistan who felt no pain, and guess what he did?

He performed street theater.

He died before his 14th birthday.

He jumped, for money, off a house roof.

He knew it would be painless.

The study of his DNA revealed he has a mutation in one gene.

It makes a protein that transmits the pain signal from the periphery-- your finger, or your skin-- through the spine to your brain.

You get rid of that gene, you cannot transmit the signal, you feel no pain.

Why?

Well, I'll give you a legitimate reason.

Pain due to cancer is terrible, especially if it's terminal cancer and we know a person has months to live.

Why not get rid of that gene?

And I'm sure this will be-- I am sure this will be.

We will have gene editing of that gene to treat cancer pain.

Now... Do I want a scenario where there are parts of the world where special forces soldiers are made immune to torture?

♪ ♪ REGALADO: I don't think my job is that different than what scientists do.

There's a lot of kind of hunting around, hunting and pecking, you know, looking under things, turning over stones.

And then eventually, you know, you kind of get on the scent of something, and then that's when the fun starts.

Before science gets published, it circulates among scientists.

The papers go out for review.

Someone passes it to somebody else.

Like, they have a certain circulation, and so I'd gotten onto the trail of these papers coming out of China.

This was the first case where someone had said about, you know, "I'm gonna use CRISPR, and I'm gonna modify a human embryo."

♪ ♪ They had knocked out CCR5.

This is a receptor that, if you don't have it, you can't get infected with H.I.V.

But think about what they were proposing.

They said, "We're gonna make someone who's immune to H.I.V."

♪ ♪ Once I started digging into it, I found more examples of people that were thinking along these lines.

John Zhang runs the third- or fourth-biggest fertility clinic in the country, and then he started a company called Darwin Life.

He said that he was enthusiastic about the whole idea of designer babies.

He basically said that, "Of course, that's the whole point."

There was a company called OvaScience that I discovered a tape recording that they had put on their own website of a investor meeting.

MAN: We will be able to correct mutations before we generate your child.

It may not be 50 years, actually.

It may only be ten, the way things are going.

♪ ♪ DOUDNA: I ended up having several dreams that were very intense for me at the time, where I walked into a room and a colleague said, "I want to introduce you to someone, "and I want you to tell them...

They want to...

They want to know about CRISPR."

And I walked into this room, and, and it was...

There was a silhouette of a chair with someone sitting with their back to me, and as they turned around, I realized with horror that it was Adolf Hitler, you know?

And he leaned over, and he said... "So tell me all about how Cas9 works."

♪ ♪ I remember waking up from that dream and I was shaking.

And I thought, "Oh, my gosh, I mean, what have I done?"

PORTEUS: Five-and-a-half years ago, it was recognized that we could take the CRISPR system out of bacteria and move it first into a test tube and then into mammalian cells, and use it as a tool for genome editing.

The Cas9 protein is gonna make the cut in the DNA.

(voiceover): We are correcting the sickle mutation in blood cells.

So if it's a woman, their eggs are not corrected.

If it's a man, the sperm is not corrected.

That change will not get passed along to future generations.

So they will be cured, but their children might get the disease, as well.

Now we need to give the cell another piece of DNA, except instead of having the T...

It has an A.

(voiceover): So why not just do it so that the diseased gene never gets passed along to future generations?

And there are some people out there who think that's all we should do.

But we may be creating things that we can't put back into the bottle.

(machine whirring) DALEY: When we engineer gene changes into my blood or into my skin, those gene changes die with me, but the germ cells-- sperm and eggs, embryos-- those cells are very different.

They're part of what we call "the germ line."

If we engineer gene changes into my sperm, they're passed to my son.

They're passed to his son and forever.

♪ ♪ URNOV: My colleagues and I wrote a fairly strongly worded piece in "Nature" with the fairly unequivocal title, "Do Not Edit the Human Germ Line."

We proposed that there be an unconditional moratorium: Don't edit human embryos, don't use edited sperm and eggs to make human embryos-- just nothing.

We must understand that when we authorize research on human embryo editing, we are enabling, ultimately, human embryo editing for human enhancement.

That's what we're doing.

We're putting the recipe out into the world.

The debate that's being had is whether society should go in this direction.

Should you be allowed to make a genetic change into the next generation that'll then go on to other generations?

The gene pool, like nature itself, is kind of a common good.

I used to have a T-shirt, and it had a little... A guy that was kind of a DNA spiral, right?

But he was the lifeguard and he's blowing a whistle, and he says, "Hey, you, get out of the gene pool!"

I loved that shirt.

FILM NARRATOR: Baby shopping.

Imagine being able to program the I.Q.

of a baby.

(Mussorgsky's "Night on Bald Mountain" playing) Will we be sitting at computer terminals like this one punching up the traits we would like in our children, like the shape of their faces or the color of their eyes?

CHARO: Well, you know, the fear that everybody focuses on most is this whole, this designer baby business.

(music continues) WOMAN: We're turning reproduction into production.

We're turning children into consumer products.

CHARO: Every time there's a new technology, we hear the same concerns.

If there's a market for cloning, there is no force on Earth that will keep buyer and seller apart.

(music continues) MAN: Perhaps Saddam Hussein would like to give birth to himself.

(music continues) CHARO: With CRISPR, even reputable magazines could not resist the temptation.

A little thing that says, "High I.Q."

As if we know what intelligence is, let alone how to measure it, let alone how to design it.

Why do we keep ignoring the fact that we've seen the same argument every decade for the last five decades?

And these nightmares, they haven't come to pass.

(music fading) We are capable of really evil things, but we don't need technology to commit evil acts.

If the goal is genocide, if the goal is eugenics, if the goal is discrimination, there will be another way to do it and it will be found.

I kind of divide the world into the bio-optimists and the bio-pessimists.

(theme from "Star Trek: The Original Series" playing) SHOW NARRATOR: Space: the final frontier.

CHARO: I grew up with the original "Star Trek," and have been a devoted follower of all of the "Star Treks" since then.

I've read pretty much every "Star Trek" novel.

Don't get me started.

It is a vision of progress and the potential of science to make life better.

There are other people who have read the cautionary tales.

RICK DECKARD: A blade runner's job is to hunt down replicants, manufactured humans you can't tell from the real thing.

CHARO: But I don't think the technologies are inherently good or evil.

The technologies are tools, they are power.

What you do with the power determines if the result is something that we applaud or something that we deplore.

But it's not the tool that determines the end point.

It's the user.

MAN: Now here are 23 representing mother's chromosomes, 23 for father's.

Now, we put them together.

(chips clattering) BALTIMORE: Our way of determining the inheritance of the next generation is a lottery.

And it's a perfectly good argument to say, "I would rather determine it than take a lottery."

Well, I think the right way to say it is that sex is for recreation and science is for procreation.

♪ ♪ 50 years from now, people may say, like, "I can't believe those barbaric people "in the early 21st century, "they were having kids this crazy, old-fashioned way.

"They were just, like, rolling the dice with their kids' lives."

We've gone through in vitro fertilization.

We've harvested the eggs.

It's not uncommon to produce multiple viable embryos.

Which one do you choose?

One possibility is, "Yeah, just, we'll just roll the dice.

We'll just-- I'll just point at one."

♪ ♪ Another option would be I run some fancy genetic tests.

GREELY: Pre-implantation genetic diagnosis is the process of doing genetic tests on an embryo.

When I talk to most people about it, they think it's science fiction, but it was first used clinically in 1990.

♪ ♪ With today's technology, you've been limited to looking at only a handful of traits.

But soon, genome sequencing will become cheap enough, easy enough, and accurate enough that you'll be able to learn everything genetics can tell you.

♪ ♪ HSU: In the future, let's imagine that CRISPR gets really, really good.

Maybe you don't need to produce lots of embryos.

Maybe you just produce one, but you can make whatever edits you want to it.

♪ ♪ KELSEY MCCLELLAND: So the carrier screening that I was talking about earlier tends to focus on disorders that show up early.

(voiceover): Everyone wants to have a healthy, perfect baby.

I think that's a universal truth.

You know, "How can I make sure "that my child will be healthy?

"How can I make sure that, you know, "they're gonna have some of these positive traits, "that they're gonna do well, they're gonna learn well, and...?"

Looking at this family history, certainly, I... (voiceover): The opinion is that information is good, and almost everyone that talks to me wants more information, and even wants more-- like, we'll give them a whole bunch of information, and they even want more.

WOMAN (on phone): I know my grandmother also... MCCLELLAND (voiceover): I actually first heard about genetic counseling from my mother.

Hemophilia A is the condition that runs in my family.

It's a genetic bleeding disorder.

There is a gene on the X chromosome.

It encodes for a protein called factor VIII.

When factor VIII isn't working, you can have a bleed that will lead to death.

If I decide to have children naturally, without reproductive technology, I am putting that child at 25% risk to have a really severe disorder.

That responsibility feels like it's on me.

It takes it from the universe's decision to my decision.

Today, I'm unusual, because I know that I'm a carrier of a genetic condition, but soon, everyone will know genetic information about themselves.

INTERVIEWER: What about the cost of it?

In the short term, there's a disturbing possibility that people with means will be availing themselves of this technology, and people who don't have those means will not.

So I kind of hope for a future where government makes it free for everybody.

You would have a generally healthier population, maybe longer-lived population on average, maybe slightly smarter population on average.

So if you have a smaller fraction of your population with Down syndrome, the average intelligence is a little bit higher, and, you know, society might run a little bit more efficiently if people are a little bit smarter.

What is the bearing of the laws of heredity upon human affairs?

Eugenics provides the answer, so far as this is known.

Eugenics seeks to apply the known laws of heredity so as to prevent the degeneration of the race and improve its inborn qualities.

Well, the concept of eugenics, if you, if you go way back, it really just means good genes.

The idea is that the human race could improve itself.

(speaking German): HSU: It was, of course, hijacked, and when people today talk about eugenics, they think specifically of the Nazis, of Nazi Germany, of compulsory sterilization, where, by force, people were compelled to be sterilized or killed because the state didn't like their genes.

There was shock last month over the revelation that the State of Virginia sterilized thousands of persons between 1922 and '72 in a program aimed at ridding the state of so-called misfits.

What we're talking about here, where we're being paid to do these genetic tests by loving parents who want to have a healthy child, to equate that with Nazism is, I think, just not, not just stupid, but actually insane.

I've taken the liberty of eradicating any potentially prejudicial conditions: alcoholism and addictive susceptibility, propensity for violence, obesity, et cetera.

We didn't want-- I, I mean, diseases, yes, but, uh...

Right, we were just wondering if, if it's good to just leave a few things to, to chance.

You want to give your child the best possible start.

Now, keep in mind, this child is still you, simply the best of you.

(medical device beeping) PALMER WEISS: My greatest fear in life, honestly, I, my two greatest fears, going back to me wanting to be a mom at the age of five, my first-greatest fear is that I wouldn't be able to have a child, and my second-greatest fear is that something would be wrong with my child.

ETHAN WEISS: Okay, good job, not too much water.

Oh, careful, sweetie.

PALMER WEISS: With Ruthie, I started seeing that she kind of wasn't tracking.

(squeals) When I would feed her, her eyes would slide back and forth.

PALMER WEISS: Hi... And then one day, I went to my friend's house, and her baby looked me right in the eyes.

And I came home to Ethan and I said, "There's something wrong."

ETHAN WEISS: We did genetic testing.

She inherited one mutated copy of this OCA2 gene from me and one from Palmer.

I don't think I even really understood that people with albinism had such impairment of their vision.

PALMER WEISS: It's kind of like wrapping Saran Wrap over your eyes with Vaseline.

Very, very hard for her to see.

Hi.

PALMER WEISS: Now I just, like, wanted to protect her.

Like, this isn't true, this isn't happening.

It was horrible... (laughs) It was bad.

PALMER WEISS: One, two, three, four.

Okay, Ruthie, Ruthie!

Whoa!

(laughs) Hi.

(laughing) ETHAN WEISS (voiceover): She was really easy and happy.

(water splashing) PALMER WEISS: Whoo!

ETHAN WEISS: And early on, I think we wondered if she was sort of, I don't know, protected by the fact that she couldn't see a lot.

RUTHIE: Look, I have a flashlight!

ETHAN WEISS: That the world wasn't as noisy to her.

Blue!

Light it, light it!

ETHAN WEISS: She was smart and talkative.

ETHAN WEISS: Come here, Yoda.

ETHAN WEISS: Super-curious.

(laughter) (laughing) PALMER WEISS: You don't know what you don't know.

You don't know that, even though it's going to be different than what you thought, you don't know, you know, maybe how much better that's going to be.

♪ ♪ (choir singing) ♪ ♪ I want to be a professional basketball player, but I don't think that's gonna happen.

(indistinct chatter) Can I hold him?

"Mission is simply one..." ETHAN WEISS: Well, I mean, I've known about CRISPR from the perspective of being a doctor probably since the first publications in whatever it was, 2012.

Oh, they've come to teach the Natives... ETHAN WEISS: It really didn't intersect with our own world, with Ruthie, until probably about a year and a half ago, when I read something on Twitter.

♪ ♪ A scientist who I respect a lot said he thought that in one or two generations, that all children would be born with all of these genetic abnormalities edited out.

(indistinct chatter) PALMER WEISS: I know people who have children who have really debilitating diseases that make their children suffer, make their families suffer a lot, so I totally understand the desire to change that.

But the rest of it scares me to death.

(indistinct chatter) PALMER WEISS: I don't know where you draw the line between not having albinism and deciding your kid needs to be an extra foot taller so they can be a good oarsman and go to Yale.

You know, where-- where is that line?

Who's going to draw that?

We're maybe a society who is afraid of things that are different or afraid of people who are different, afraid of people who have needs.

I worry that when we're manipulating future generations, those opinions are going to be passed on.

DALEY: You know, we as a society may think that doing better on the S.A.Ts.

is better than doing worse.

Being taller, being handsomer, being more creative, being more courageous, those are traits that we would want to potentially select for.

Should we go there?

Is there an inevitability to going there?

You know, sometimes, I'm invited to give a talk on, like, kind of futuristic science things, and I've had tall, blonde trophy wives come up to me after the talk and say, "Wow, that was incredible.

"That was an incredibly interesting talk, "but don't you think there's a problem with all this?

"Won't every parent just select their kids to be tall and blonde?"

The geeks all come up to me and say, "Isn't this dangerous, "'cause all the parents are gonna select for the smartest kid they can possibly get?"

'Cause that's what the geeks think is cool.

You know, probably if you were talking to some NFL coaches, they'd say, "Oh, what, everyone's gonna, "everyone's gonna select their kid to be 6'5" and run a 4.2 40," you know?

So, um, there will be a wide range of what people think is the right thing to select for or engineer for.

And, actually, there's nothing wrong with that, right?

Let a million flowers bloom.

On this estate 30 miles north of San Diego is housed a sperm bank said to be made up exclusively of donations by Nobel Prize-winning scientists.

The bank's founder will consider for fertilization only women of high intelligence.

You don't know about the Nobel sperm bank?

(laughs) REPORTER: Businessman inventor Robert Graham adds liquid nitrogen once a week to a lead-shielded sperm repository in an underground concrete bunker in his backyard.

GRAHAM: The more good genes in the human gene pool, the more good individuals will come out of it.

We aren't even thinking in terms of a super race.

CHARO: The so-called genius sperm bank, a sperm bank to provide women, for free, with donor semen from men that they viewed as geniuses.

We utilize sources such as this: "Who's Who of Emerging Leaders."

CHARO: Very few women actually went ahead and took advantage of this offer to be given superior sperm for free.

I did a tour of sperm banks for the U.S. Congress.

I think I'm the only person who's ever gone on a congressionally financed tour of California sperm banks.

Despite the fact that the donors are described taller, skinnier, you know, better-looking or not, people tended to pick somebody who looked like their partner, no matter how imperfect, because the emotional importance of the connection outweighed any notion of improvability or perfectibility.

If I were trying to have a child and my partner was light-skinned, short, with eczema, I would have had a child with a guy who was light-skinned, short, and prone to eczema.

INTERVIEWER: But what if you could take that guy's sperm and edit those specific things out?

Could I change his sperm so it's still him, but a better him?

Exactly, yeah.

Right?

Maybe, but every change does come with risks that you'll make changes you didn't intend, so I think it'd be a long, long time before you would take that risk for anything other than something that was pretty significant.

But I might want to take advantage of editing something out that would give my kid a very strong chance of developing a severe cancer, even if it's 40 years in the future.

Yeah.

So maybe that will happen.

CHARO: This committee's gonna be looking at both somatic and germ line applications of gene editing.

(voiceover): The committee that I co-chaired for the National Academy of Sciences, we were asked to look deeply at whether or not there was something intrinsically unethical about manipulating genes in a way that makes them heritable.

Significant degree of uncertainty...

This should be the goal of society, to promote a better life for all and to ensure that everybody can live a life in dignity and freedom.

Can this be achieved by germ line gene editing?

My view is no.

REGALADO: The American Medical Association, a bunch of European countries, you know, any number of organizations all had positions, like, meddling in the germ line would be wrong.

It would be unethical.

But they all said those things at a time when it couldn't be done, so it was easy to say.

It was a gimme, right?

And then as soon as it comes that you can do it, then the positions change.

WOMAN: Huntington's lurks in our DNA like a time bomb.

It would really eliminate a scourge in the world, so I would say go for it.

REGALADO: At the big National Academy meeting, there was not a good representation of patients, but the few who did speak were definitely in favor.

I say, yes, it is worth pursuing in a safe and rational manner.

Definitely, let's go.

Anything that will stop my child from suffering, I'm for.

You know, draw this ethical line wherever you want, but don't draw it in front of my disease.

He was six days old.

REGALADO: I remember one woman told a story about a child that she had and died of an inheritable disease.

(voice trembling): He had seizures every day.

We donated his body for research.

(crying): If we have... (sniffs, inhales): The skills and the knowledge to fix these diseases, then freaking do it.

CHARO: The statement of task demanded that we try to follow the evidence and follow the logic, not that we follow the politics.

We said, "We conclude it is not intrinsically evil."

It is what we called ethically defensible, but we understood that this was now a break from the past in the thinking on this topic, yes.

In Genesis chapter one, we discovered the concept of the Imago Dei, being in the image and likeness of God.

(congregation murmurs) What does that mean for this science where we have the capacity to edit in some things, perhaps, that we think are important?

Are we playing God?

♪ ♪ (birds cawing) (chirping) RACHEL CARSON: The balance of nature is built of a series of interrelationships between living things and between living things and their environment.

(insects chirping) ♪ ♪ Now, to these people, apparently, the balance of nature was something that was repealed as soon as man came on the scene.

♪ ♪ YANG: This is Laika, this is Nova, and this is Joy.

Our pig is the most advanced genome-modified animal running on the Earth.

(murmurs) CHURCH: The babies that came out of that are now adults, and the adults are having their own babies, so it seems like making that many edits is completely compatible with a happy, healthy pig.

(machines whirring) I tell people to be visually underwhelmed by my lab.

It's just a bunch of small rooms with usually very few people in them.

But in terms of what I see, it's very exciting.

(laughs softly) ♪ ♪ I've never really felt the "mad scientist" was realistic for anybody that I knew, including myself.

My lab has been accused of taking science fiction and turning it into science fact.

I consider that very high praise.

But turning science fiction into science fact is not mad.

It actually can be quite useful.

♪ ♪ "Aging reversal" is the term that I prefer.

You know, I'm 63 years old.

I feel like I just barely got trained to do my job last year, and so now you're gonna pull the plug and recycle me.

That doesn't make sense.

(mouse clicks) We need to be cautious in that, you know, there's a, there's this whole population problem, so we can do that if we have a place to put all those people.

♪ ♪ Almost everything we do, people just think, "This is goofy, this is not feasible, it's science fiction."

But I think, originally, people thought that sequencing human genomes inexpensively was a pipe dream.

INTERVIEWER: I can't not ask you about mammoths because there's a bunch of them behind you.

Yeah, that should be up at the top of the list of things that seem, uh, quixotic or misguided.

So in the Mammoth Project, we read the ancient DNA, decide which genes we're going to resurrect, put those into the Asian elephant's cells, and then we're developing technology that is not yet working to make, take those embryos all the way to term.

Then we scale that up to make a herd of these things, maybe 80,000 of them, to repopulate the tundra.

IAN MALCOLM: Don't you see the danger, John, inherent in what you're doing here?

Genetic power is the most awesome force the planet's ever seen, but you wield it like a kid that's found his dad's gun.

I don't think you're giving us our due credit.

Our scientists have done things which nobody's ever done before.

Yeah, yeah, but your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they didn't stop to think if they should.

(laughs softly): Well, I often try to avoid talking about "Jurassic Park," but I'll, I'll give you this.

You know, "Jurassic Park" was about hubris.

What species is this?

Uh, it's a velociraptor.

RYAN PHELAN: It's just the opposite of what scientists like George Church and others that we work with are thinking about.

When people say, "Aren't you playing God?"

my real reaction is, nobody is playing in this field.

Nobody is toying with it just to see if it can happen.

You know, in order to even fathom bringing back an extinct species, there's no end of engineering that has to happen, and it is all novel, important, new science that can be used to protect any species, endangered as well as extinct.

♪ ♪ Once you realize the magnitude of humans' impact on the environment, you know, it's hard for me to say that we can't try to correct it.

We can't have our head in the sand.

We have a responsibility to use our human ingenuity and our human skills and our wherewithal.

Sometimes it's leaving nature alone, and sometimes it might be intervening.

♪ ♪ MAN: So the gene we've edited controls how the pores on the underside of the leaves open and close.

In the non-edited plant, the stomata or pores will stay open during the hot, dry conditions.

Water is lost, and then these leaves lose water.

They wilt, and they roll.

In the edited plant, those stomata pores close sooner under dry conditions and the water is retained inside the plant.

♪ ♪ GREELY: We have been messing with nature ever since we came out of the trees.

Most of the lifeforms we eat are things we've made.

Corn used to be a grass.

Tomatoes used to be tiny little berries that were bitter.

Geneticists changed that.

Now, we didn't call them geneticists.

We called them farmers.

INTERVIEWER: Do you think among these people there was anyone that would be fair to call a scientist?

IAN HODDER: Well, that's a really interesting question.

I think there's lots of different types of science that were involved.

The first people who invented pottery were really chemists, in a way, um... And certainly the people who were inventing agriculture and control, controlling plants and animals, they were biologists, you know, botanists and biologists, in our sense.

You know, you can see people trying things out.

What is the best way to grind grain, and how do you make bread?

You know, that was invented here.

To work that out... (chuckles) Is really not, is not straightforward.

(brushing) HODDER: In this period of time, something more modern-like in terms of our relationship with nature was beginning to emerge.

As far as we understand it, hunter-gatherers had a relationship of equality with nature and had to look after nature, and if you hunted an animal, you would have to give a gift to nature to thank it for the animal that you'd been given.

And then as people started domesticating plants and animals, they started having a new relationship, where they were dominating and controlling the natural world... (sheep bells rattling) That made it something that you could transform.

♪ ♪ We definitely see great advantages in genetic engineering, as agriculture, you know, was a great, a great advance.

Certainly, it's the building block of civilization as we understand it.

But it definitely comes with its negatives.

♪ ♪ You could say that the long-term consequences were pollution and environment degradation and so on and so forth, but you would have had to be very far-seeing, you know, 9,000 years ago to realize that, that that was what was gonna happen.

CHARO: These things creep in slowly.

It's not like everybody was hunting and gathering, and then next year, somebody said, "Oh, let's farm," right?

It happened slowly, and so it is disruptive, but it creeps up on people.

You don't realize it's disruptive until you look backward.

Often you don't realize that you're in the middle of a revolution until after the revolution has occurred.

Right?

So I don't know where we are right now.

It'll be interesting to see.

I hope I live long enough to see it.

INTERVIEWER: Do you think you want to have kids?

I have too many siblings for that.

The answer's probably gonna change, but for now, probably not, no.

I'm not crazy.

They're saying maybe one day with CRISPR, they could go in and change the gene in the embryo so that the kid, when it's born, doesn't have sickle cell.

Hmm.

I guess that's kind of cool, that they're thinking that it can do that in the future, but I think that would be up to the kid later.

What do you mean?

There's a lot of things that I learned having sickle cell just because I had it.

I learned patience with everyone.

I learned, uh, just to be positive.

So you don't wish that you never had it.

I don't wish that I never had it, no.

I don't think I'd be me if I didn't have sickle cell.

♪ ♪ GREELY: Sickle cell's a really interesting, unusual genetic disease.

If you've got two copies of the sickle gene, you're really sick, and without modern medicine, you die young.

If you've got two copies of the normal gene, you don't get sickle cell at all.

It turns out, though, that if you've got one sickle gene and one nonsickle gene, you make cells that are somewhat sickle?

You're not sick, but the organism that causes malaria doesn't like those red blood cells.

Having a sickle gene is protective against getting severe malaria, so in the environment where there's lots of malaria, it's better to be sickle cell trait than not to be sickle cell trait.

GREELY: And that's why you see sickle cell anemia in sub-Saharan Africa, but you also see it in the Mediterranean, in Greece and in Sardinia.

It's because they had mosquitoes and malaria.

PORTEUS: The relationship between our genes and our environment is incredibly complex.

"Thanks, little brothers..." PORTEUS: And we don't understand that.

(birds squawking) ZHANG: I think we have to have humility.

Nature is one of the greatest inventors of all time.

What we can do is, is a very, very insignificant fraction of what nature has already done.

Nature invented CRISPR.

PORTEUS: So now we're mixing the cells with the CRISPR.

That's beautiful.

Once it's into the cell, that starts the editing process.

We can't see that, we just know it happens.

DAVID SANCHEZ: I don't know how, out of all the genes that you have, that it targets the one that's doing sickle cell and not the thing that's making you grow hair.

Oh... (voiceover): But it does, apparently.

Like, that's cool.

(laughs) ♪ ♪ DOUDNA: You have to appreciate that this is a technology that's only about five years old, but it's been deployed incredibly rapidly.

(voiceover): We've never had the ability to change the fundamental chemical nature of who we are in this way, right?

And now we do, and what do we do with that?

DOUDNA: It does make us really think deeply about what it means to be human.

What do we value about human society?

And I know for myself... URNOV: The things that make us most human are some of the most genetically complex, which is kind of a relief.

Creativity... (laughs softly) URNOV: Emotionality.

Love.

Now, I want to be clear: they all have a biological basis.

They are all written in our DNA.

♪ ♪ But we are a very, very, very long way away from being able to edit the person.

INTERVIEWER: Do you think that day will come?

URNOV: I do, but I'm hopeful that we will mature as a species before we get this incredible technology to play with for our own detriment.

I am hopeful for that, yes.

Is that hope based in fact?

We'll see.

How might we like to change our genes?

Perhaps we would like to alter the uneasy balance of our emotions.

Could we be less warlike, more self-confident, more serene?

Perhaps.

(growling softly) SINSHEIMER: Ours is, whether we like it or not, an age of transition.

After two billion years, this is, in a sense, the end of the beginning.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ANNOUNCER: To order this program on DVD, visit ShopPBS or call 1-800-PLAY-PBS.

Episodes of "NOVA" are available with Passport.

"NOVA" is also available on Amazon Prime Video.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪

The "Holy Grail of Yogurt" is CRISPR

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S47 Ep11 | 4m 1s | Five years before anybody was talking about CRISPR, Danisco had a breakthrough. (4m 1s)

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S47 Ep11 | 28s | We can now edit the human genome with a tool called CRISPR. But how far should we go? (28s)

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S47 Ep11 | 2m 8s | We can now edit the human genome with a tool called CRISPR. But how far should we go? (2m 8s)

Living with Sickle Cell Anemia

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S47 Ep11 | 3m 22s | Sickle Cell Anemia is caused by a single change in the DNA sequence. (3m 22s)

CRISPR Gene-Editing Reality Check

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S47 Ep11 | 19m 13s | CRISPR gene-editing technology is advancing quickly. What can it do now—and in the future? (19m 13s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S47 Ep11 | 3m 24s | CRISPR is part of bacteria's natural defense against viruses. (3m 24s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- Science and Nature

Capturing the splendor of the natural world, from the African plains to the Antarctic ice.

Support for PBS provided by:

Additional funding for "Human Nature" is provided by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. Additional production support is provided by Sandbox Films, a Simons Foundation initiative. Major funding for NOVA...