Chasing Carbon Zero

Season 50 Episode 6 | 53m 31sVideo has Audio Description

Here’s how the U.S. could reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2050.

Can the U.S. reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 and avoid the biggest impacts of climate change? Experts say it can be done. Here’s the technology that could get us there.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Additional funding is provided by the NOVA Science Trust with support from Anna and Neil Rasmussen, Howard and Eleanor Morgan, and The Arthur Vining Davis Foundations. Major funding for NOVA...

Chasing Carbon Zero

Season 50 Episode 6 | 53m 31sVideo has Audio Description

Can the U.S. reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 and avoid the biggest impacts of climate change? Experts say it can be done. Here’s the technology that could get us there.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch NOVA

NOVA is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

NOVA Labs

NOVA Labs is a free digital platform that engages teens and lifelong learners in games and interactives that foster authentic scientific exploration. Participants take part in real-world investigations by visualizing, analyzing, and playing with the same data that scientists use.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship♪ ♪ MILES O'BRIEN: What would it take to convert our technology and reach a once-unimaginable goal?

We are at a critical point in our history right now.

O'BRIEN: Zero-carbon by 2050.

So what do we need to do to actually meet that goal?

O'BRIEN: We'll need to move fast.

Shall we?

Yeah, let's go.

O'BRIEN: And in some ways, we are.

Let's go fast.

♪ ♪ We need our electricity, our power plants to be zero-carbon.

O'BRIEN: So we have to keep floating new ideas.

HABIB DAGHER: There's enough offshore wind capacity to power the country four times over.

O'BRIEN: And giant batteries to keep everything still going.

YET-MING CHIANG: This is something that just a few years ago was considered impossible.

O'BRIEN: Running our homes without lighting a flame.

DONNEL BAIRD: We want to turn buildings into Teslas.

We want to make them smart, green, healthy, all-electric.

O'BRIEN: No technological breakthroughs required.

We just have to get down to business right away.

O'BRIEN: "Chasing Carbon Zero," right now on "NOVA."

♪ ♪ O'BRIEN: We're departing late on a long journey.

Our destination is 2050.

Scientists say that's the deadline for putting the brakes on greenhouse gas emissions.

It is arguably the most important challenge humanity has ever faced, and that is why I want to understand how we'll get there.

I'm Miles O'Brien, and I've been a reporter on the climate beat for 30 years.

I've borne witness to it all: dead coral reefs, melting ice, rising seas, catastrophic storms.

The main evacuation center in New Orleans is the Superdome.

O'BRIEN: Epic wildfires.

I've watched this slow-motion train wreck.

And so have you.

And now the question is, can we stop what we started at the dawn of the industrial age before it's too late?

♪ ♪ To do that, as much as we can, we need to stop burning things.

♪ ♪ Stop emitting greenhouse gases into our atmosphere.

Or we will have made our planet a very uncomfortable place to live.

But how to avoid that?

What is the road to carbon-zero?

It's a long trip, but it's not beyond our range.

♪ ♪ Let's start in Detroit.

The Motor City.

My hometown.

♪ ♪ A city built on the power, utility, and reliability of internal combustion is now embarking on a new journey.

Welcome to the Electric Motor City.

It's my first stop, because on the road to zero, I'm going to need a ride.

I want to test-drive with you.

This will be a special ride in the Lightning.

All right?

Let's go!

With Lightning's mama, so to speak, right?

(laughs): Sounds good.

O'BRIEN: I met Linda Zhang at the Ford Rouge Center west of downtown.

She is the chief engineer for the all-electric Ford F-150.

Shall we?

Yeah, let's go.

O'BRIEN: The truck they call the Lightning.

ZHANG: Let's go fast.

O'BRIEN: I gotta tell you, you never get tired of that, right?

That's always a fun and smooth acceleration.

Yeah-- yeah.

What is the official zero to 60 anyway?

It's just under four seconds.

Really?

It's pretty exciting.

ZHANG: That torque is really instant.

You step on it and you go.

O'BRIEN: Electric motors don't just cut out tailpipe emissions from vehicles.

They're also much more efficient than internal combustion engines at converting energy into motion-- 85% to 90%, as opposed to about 40%.

And the acceleration is lightning-fast.

ZHANG: The propulsion's definitely there.

So it's almost, like, a shame if you don't use it.

O'BRIEN: Demand is strong.

O'BRIEN: So how often are you seeing your vehicles on the road these days?

It's still a small percentage, right?

Um, yeah, there's definitely more and more on the road.

And I always love seeing them on the road.

I have to be honest with you, it's like seeing, um, seeing, you know, one of my kids off.

(both laughing) ♪ ♪ O'BRIEN: The F-150 is a Ford mainstay, a vehicle favored by loyal owners who use it for work.

Did you feel like it was a risky thing to electrify something as iconic as an F-150?

Yeah, absolutely.

This was a big risk for us, but at the same time, it came with big rewards.

You know, being able to take this product that is already America's favorite truck, but electrifying it, really helps bring this into the light for, for customers that didn't know much about electrification.

We're now taking this electrification concept and really making it a mass adoption.

♪ ♪ O'BRIEN: That's happening right now.

In the U.S., more than five percent of new cars now sold are all-electric.

That may not seem like much, but it is a marketing milestone, the line between novelty and mass adoption.

But internal-combustion cars stay on the road for 14 years on average.

Reaching zero tailpipe emissions from cars and trucks will take some time.

MELISSA LOTT: So we're headed towards net zero, but we're on the local train-- need to hop over to the express.

O'BRIEN: Melissa Lott is an engineer focused on energy.

LOTT: So I take the energy used in this train... O'BRIEN: Really focused.

LOTT (echoing): Metal, plastic, paper, glass in the windows... O'BRIEN: Everywhere she looks, she sees embedded carbon.

LOTT: I can probably figure out the carbon footprint of that... O'BRIEN: It's a superpower.

LOTT: Like 20 people average per car... O'BRIEN: Or is it an obsession?

LOTT: I see energy in everything I'm looking at.

I actually enjoy it and I don't even notice it that much.

I really, it's just something that I'm running kind of in the background all the time.

So, as it turns out, this obsession actually comes in handy in my line of work.

Good to see you!

LOTT: I'm the director of research at the Center on Global Energy Policy here at Columbia University.

O'BRIEN: And that's where I met her-- I figured she can help me understand where we are in the chase to carbon-zero.

So when we look at where our emissions come from today, we see a couple of big wedges on this pie.

O'BRIEN: There are three big, nearly equal pieces of the pie.

The first one is transportation.

O'BRIEN: Transportation: planes, trains, automobiles, trucks, and ships.

The next wedge on this pie is going to be our electric power, our power plants.

O'BRIEN: Electric power: about 60% is still generated with fossil fuels.

After that, we're looking at industry, so how we create all the things that we use day to day.

O'BRIEN: Industry: manufacturing and construction.

And two smaller pieces remain.

LOTT: The rest of this pie is actually our buildings, so the homes we live in and the offices we work in.

And then also our agricultural system.

So how we produce food.

O'BRIEN: These wedges represent total greenhouse gas emissions the U.S. is releasing into the atmosphere, more than six billion metric tons a year.

What would be better?

The idea is called "Net Zero," meaning first, we reduce our carbon output as far as we can.

Then, for the most stubborn sources, develop techniques to capture and store the carbon, netting zero.

Most experts agree it's really the only way to avoid a worsening climate disaster.

The U.S. goal is to get halfway to Net Zero by 2030.

And here's a surprise-- as of 2023, we are further down the road than I thought.

LOTT: Compared to 2005, which is our baseline, we've already reduced emissions by about 18%.

And thanks to cheap solar, cheap wind, cheap natural gas replacing coal, and cheap storage, we're working our way towards 25% reduction.

♪ ♪ O'BRIEN: Getting the rest of the way to zero won't be easy.

The pie gives us an idea of how we can make some headway.

But where do we start?

Close to home: buildings.

LOTT: Buildings represent 13% of total emissions in this country.

When we look at buildings overall, there's a couple of things we can do.

We can move ahead with electrifying our buildings, with taking natural gas out of our buildings and replacing it with other technologies we have, for cooking, for heating and cooling our air, for heating our water.

O'BRIEN: So what's the best alternative?

All-electric homes.

MAN: Here you go.

O'BRIEN: On rooftops all over New York City, there is evidence that electricity is gaining currency.

In 2022, Americans bought more heat pumps than gas furnaces.

Landlord Lincoln Eccles was thinking about his son Ace when he made the decision.

We've built an infrastructure based on oil and gas.

Burning things-- that's what we're used to.

But it doesn't have to be that way.

O'BRIEN: It's the third iteration for the early-20th-century building he owns in Crown Heights, Brooklyn.

When it was built, they burned coal in a boiler to stay warm.

Now there's a heat pump for each of the 14 units.

Heat pumps work not by creating heat, but by moving it from one place to another.

Inside, there's a fluid called refrigerant that boils at 40 degrees below zero Fahrenheit.

As long as it is warmer than minus 40 outside, the refrigerant picks up heat from air as it becomes a gas.

It flows into an electric compressor, where it is put under pressure, adding more warmth to the gas.

The warm gas flows into the room unit.

As it heats the space, the gas itself condenses back into a liquid.

Now the liquid travels back out, flowing through a valve that lowers the pressure and thus the temperature.

And the cycle starts all over again.

So in the winter, it can pump heat inside.

And in the summer?

The process is reversed to pump heat outside, cooling the room.

In Lincoln's building, each unit has its own wireless thermostat.

Set the temperature, boop.

O'BRIEN: Easy enough for his son to operate.

Lincoln hopes Ace will be the landlord here someday.

O'BRIEN: So you think when Ace is your age, everything around us here will be electric?

ECCLES: Definitely.

These two behind us are green.

These developments over here, they're green.

If they could do my building, they could do every building on the block.

O'BRIEN: But heat pumps are not cheap.

And for us to reach net zero, nearly every building will need to make the transition.

So how can this technology become accessible to everyone?

That is precisely the goal for Donnel Baird.

BAIRD: If we can do one building, we can do a whole block of buildings.

And if we do a block of buildings, we can do a whole city.

O'BRIEN: He is the C.E.O.

of a startup called BlocPower.

BlocPower wants to turn buildings into Teslas.

We want to make them smart, green, healthy, all-electric.

O'BRIEN: Founded in 2014, BlocPower is making it more affordable for landlords to make the switch.

Lincoln Eccles' old building is one of about 2,000 conversions the company says it has spearheaded so far.

BAIRD: We have everything that we need to green all the buildings now.

That's why it's so important that we focus on buildings, because we don't need any more innovation.

You know, when there is some data... O'BRIEN: Donnel was able to mix the pressing needs of a landlord with a bad boiler-- and a planet boiling over-- into something attractive to Wall Street investors.

It's a company committed to executing the conversion at scale, bundling a lot of projects together to lower the cost and lower the risk.

BAIRD: We show up and we say, "Look, "we've got capital from Goldman Sachs and Microsoft "to finance moving you to a functioning, better system.

"And it costs you nothing.

"As a matter of fact, you're going to save money "because the payment that you make to us over 15 years "is going to be less than what you would pay "to the oil company or to the gas company as an alternative."

O'BRIEN: The arithmetic relies on incentives from the government and assumptions that the cost of heat pump manufacturing and installation will decline.

For BlocPower, the goal and the risks are big.

He's in favor!

O'BRIEN: Lincoln Eccles says it's working for him.

ECCLES: They just made it work at the end of the day.

It was a lot of back and forth, but it can be done.

It's not an impossible task.

O'BRIEN: BlocPower's mission is altruistic, but it is also a startup hoping to make a profit.

It makes a percentage on financing, charges fees to manage electrification projects, and eventually hopes to market the very heat pumps it installs as producers of carbon credits.

BAIRD: This is capitalism deciding that there are trillion-dollar companies to be made addressing the climate crisis, that entrepreneurs who figure it out are going to make money.

And there's going to be so much money to be made by bringing those solutions into the economy that we are going to make our venture capital returns.

And you can choose to do business and make profits in a sector and in a way that helps people.

O'BRIEN: Spoken like the Columbia Business School grad that he is.

That, combined with his roots in Bedford-Stuyvesant, are what gave him the inspiration for BlocPower.

The furnace in his building never worked.

Ultimately, when it got really cold, we'd have to heat our apartment with our oven.

We would turn on the gas oven, turn on the burner on top of the oven, open up the oven door to let the heat into the apartment.

I really empathize with a lot of our customers, because I know how uncomfortable it is to be cold, and how difficult it is to, like, sleep through the night when you're freezing.

O'BRIEN: The road to zero, by definition, must pass through neighborhoods like this.

BAIRD: There isn't going to be a green revolution in America without working-class and poor people.

So there must be a financial solution that includes them.

O'BRIEN: In New York City, buildings account for around 70% of greenhouse gas emissions if you include electricity.

The city is aiming for carbon neutrality by 2050.

And there are several laws designed to make that happen.

One eliminates the burning of fossil fuels in all new buildings by 2027.

But there is an important asterisk: the city's commercial kitchens are exempt.

Here, gas stoves and ovens dominate.

So the biggest polluter in these buildings are the kitchens.

So why would you exempt the biggest polluters?

O'BRIEN: Chef Chris Galarza has years of experience working in kitchens at popular high-end restaurants.

You're dripping sweat!

O'BRIEN: In this case, art has found a recipe for imitating life.

Whether it's "Hell's Kitchen" or "The Bear," Hollywood has made it clear to all of us, if you can't take the heat, you really should get out of the kitchen.

What you notice is as soon as you open the door going from, say, the dining room to the kitchen, is this wall of heat.

I have looked down at my thermometer in my chef coat and it would read 135 degrees Fahrenheit.

So I can't tell you how many times that, after a rush, we would be rushing to the bathroom to throw up.

O'BRIEN: The main ingredient of natural gas is methane, and research shows burning it in a kitchen can be harmful to human health, because it triggers a reaction between nitrogen and oxygen which creates nitric oxide and nitrogen dioxide, pollutants collectively known as NOx gases.

They can cause all sorts of cardiovascular and respiratory illnesses, including asthma.

The no-gas alternative looks and feels very different.

It's lunchtime at Chatham University's Eden Hall campus near Pittsburgh.

What I need is the cook's tour-- literally.

Okay.

O'BRIEN: The kitchen here is quiet, cool, and all-electric.

This is our four-burner range, like, there's two of them.

This is the workhorse of the kitchen.

This is now the tilt skillet, also induction.

Two steamers, two electric convection oven, triple-deck oven with two built-in proofers for breads, pizzas, pastries, and things like that.

O'BRIEN: Chris was the executive chef here in 2016 when the school opened this dining hall.

The university built the Eden Hall campus as a showcase for sustainable solutions.

So there's not a single lit flame in this kitchen.

Not a single one.

O'BRIEN: The cooktops here use a technology called induction.

I had my own bias, as well, and it wasn't until I experienced induction cooking that I became a fan.

O'BRIEN: Traditional electric stoves create heat by simply resisting the electric current.

But newer induction cooktops use electricity to create a magnetic field.

The electrons inside pots and pans that contain iron try to align with the magnet, vibrating tens of thousands of times per second, creating friction and heat.

The result is better energy efficiency, faster cooking, and no combustion fumes.

They have caught on in commercial kitchens in Europe and Asia, but in the U.S., chefs are skeptical.

GALARZA: The rest of the world is looking at us going, "What are you complaining about?"

Because effectively, we're arguing about how to get a piece of metal hot so we can cook.

O'BRIEN: The fossil fuel industry has done a good job at inducing resistance.

♪ Cooking with gas, cooking with gas ♪ We all remember the rap in the '80s.

♪ We all cook better when we're cooking with gas ♪ It's cringeworthy.

♪ Cooking with gas ♪ ♪ Cooking with gas ♪ ♪ We all cook better ♪ ♪ When we're cooking with gas ♪ There's a lot to unpack there.

♪ I cook with gas 'cause it costs us ♪ Much less than 'lectricity ♪ GALARZA: But you know what?

That was effective.

What was said in there still gets said today.

Cooking with gas is cheaper, it's more precise.

All these things, which are, which are just not true.

♪ We're cooking with gas ♪ O'BRIEN: Today, Chris is an independent consultant who travels the country promoting induction in commercial kitchens.

He gave me a quick demonstration.

O'BRIEN: Okay, so this has been in the freezer?

Correct.

So this is just to show how quickly these come up to temp.

So we're going to dump this.

Oh, yeah, it's cold.

So just getting the water off, you can tell, things are hot.

I see, oh.

How hot?

(sizzling) All right, that was in the matter of, what?

Seconds?

Yeah.

Right?

So there's no more preheating.

It's just straight hot.

And it doesn't take long.

Now your shrimp.

Got some good color on it.

Add our sauce.

(pan sizzling) And there you go.

That was dinner in about two minutes.

In a fraction of the time, and here's the beautiful thing.

We just did all of that.

Not a sweat on you.

Nothing gets hot except for the pan itself.

So it's time for us to evolve, to get together, and say, "What's better for our world?"

And cooking with a flame is not.

O'BRIEN: Dousing the home fires will take a lot longer than that stir fry, for sure.

LOTT: When we look at the buildings that will be here in 2050, most of them are already built today.

Retrofitting this building is not going to be cheap and it's going to take a lot of work and it's going to be disruptive.

But what we can do in the next seven years is set up our building codes and our regulations so that we can retrofit and build buildings in a way that is net-zero-compliant from day one.

O'BRIEN: When it is burned, the methane in natural gas is converted to carbon dioxide.

That's problem enough.

But unburned methane is an even greater concern.

It doesn't last as long in the atmosphere as carbon dioxide, but over 20 years, methane traps about 80 times more heat than CO2.

So methane is currently responsible for nearly a third of human-caused global warming.

LOTT: So when we look at overall greenhouse gas emissions, methane is a big player.

And it's also something that we can address right away.

It's one of these gases where the more and more we look at it, we realize that a ton of it is just being wasted, thrown into the air.

♪ ♪ O'BRIEN: On a rooftop observatory in West Harlem, Róisín Commane, an assistant professor in Earth and environmental sciences at Columbia, is using a suite of sensors to measure air quality.

O'BRIEN: This is like the Mauna Kea of New York, huh?

Right?

(laughs): Yes, it is.

The observatory!

O'BRIEN: We are at the Advanced Science Research Center of the City University of New York.

O'BRIEN: Do you try to make excuses to come here on nice days to check the gear?

It's usually on bad pollution days when we get dragged here, but yes, it's lovely to be here.

O'BRIEN: It's early, and chimneys in Harlem are billowing.

Puffs of proof the city that never sleeps is, in fact, waking up.

As you look out over the city, what are you looking for?

On a day like today, you can kind of see a lot of, of chimneys.

Mm-hmm.

Or you can see the smoke coming from chimneys.

Yeah, we did.

And what we've been trying to figure out is, where is all the methane coming from, and is it from these chimneys?

O'BRIEN: It's not just gas appliances.

Methane leaks from wastewater treatment facilities, power plants, and landfills.

What are the challenges you face?

Why is it so difficult?

There's so much of it.

It could be a mixture of, there's a wastewater treatment plant that has a power plant with natural gas as part of it.

And then between there and here are a whole bunch of boilers.

So everything is just mashed together so much that that's what we spend our time trying to figure out, is how to pull all that apart.

COMMANE: Well, how does it look today?

O'BRIEN: Scientists are measuring more than twice as much methane as the E.P.A.

can account for.

Well, they've got a pretty good throughput.

They're about a liter a minute each.

COMMANE: So we're either missing a sector or we're getting the wrong numbers for certain things.

And that's what I've been working on, is to try and make sure, do we have the right number?

O'BRIEN: The sensor technology has dramatically improved in the past few years, making the devices she uses much more sensitive and more portable.

COMMANE: Now we can just put this thing in a backpack and walk around and get really, really sensitive measurements.

O'BRIEN: And so she and her team carry sensors, chasing zero on foot.

♪ ♪ About 2,000 miles away, in Texas, there is another kind of methane hunt underway.

This is the Permian Basin, the largest oil field in America, about 86,000 square miles spanning Texas and New Mexico.

There are tens of thousands of oil wells here.

And there is no mystery where the methane is coming from.

This is happening because they developed the technology to frack oil and gas from shale.

If they hadn't done that, we would have converted to clean energy a long time ago.

O'BRIEN: Sharon Wilson is an environmental advocate who is bearing witness to an ongoing greenhouse gas disaster in the Permian Basin.

When oil rises to the surface under pressure, it comes with a witches' brew of hydrocarbon gases, including methane.

In the U.S., oil and natural gas production and distribution is the largest industrial source of methane emissions.

And the Permian may be the largest methane-emitting oil and gas basin in the country.

WILSON: And we call this a climate bomb.

The industry cannot stop this pollution.

Methane is a volatile gas.

It will not stay inside a closed, unpressurized system.

And so you have to release it, or it will blow the equipment up.

O'BRIEN: Methane is invisible and odorless.

Working with the nonprofit Earthworks, Sharon is using a $100,000 camera that gives her superpower vision.

I'm going to get one more video.

O'BRIEN: The camera records the spectral signature of hydrocarbons and volatile organic compounds.

So what looks like this in visible light becomes this in Sharon's viewfinder.

WILSON: I am seeing a lot of methane blasting out from that flare that is barely lit.

Unfortunately, this is not unusual.

There's just way too much methane.

O'BRIEN: Even though methane is the primary ingredient of natural gas, here in the Permian Basin, it's mostly considered waste.

To reduce methane emissions, operators are supposed to burn it in flare stacks like this.

This converts methane-- CH4-- into CO2, reducing its impact on the climate crisis.

But frequently the flare stacks flicker, falter, or fail.

Cracking down on unlit flares and enabling innovative, cost- effective leak detection systems are the cornerstones of a new E.P.A.

rule aimed at curbing methane emissions.

What, in your view, is the solution?

The best available control technology for methane is to keep it in the ground.

Never, never drill that hole in the first place, because once you drill that hole, that's where it all starts.

O'BRIEN: But is it practical to hit the brakes on oil and gas production?

If we're out of gas, can we reach the finish line?

LOTT: Even in a net-zero world, we will probably use some amount of oil and gas.

It will certainly be less than today, but we can't go from one to zero and all of a sudden just shut it all off.

♪ ♪ O'BRIEN: While we need gas and oil for now, eventually we must eliminate burning as much as possible.

And the easiest way to do that is to take fossil fuels out of power plants and off the grid.

LOTT: The question is, how are we going to get those emissions off the board?

So today, we produce a little over a third of our electricity using zero-carbon resources.

We want to get that number up by 2030 to 75%.

What we're going to see is explosive growth in both wind and solar.

Those are the big ones that are driving down emissions.

O'BRIEN: There are now more than 70,000 utility-size wind turbines on U.S. soil-- enough to power about 39 million homes.

But the best places to put the wind farms are often far from the population centers that use the electricity.

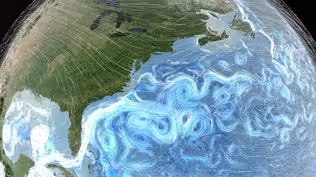

This is helping drive wind power offshore, beyond the horizon, the turbines connected to the power grid with submerged cables.

The federal government is auctioning leases for 30 gigawatts of offshore wind energy by 2030 and 15 gigawatts of floating offshore wind by 2035.

The promised electricity should be enough to power roughly 15 million homes.

Floating wind is a relatively new idea that opens up waters deeper than about 200 feet, which is the limit for turbines fixed to the bottom.

This technology appears ripe for rapid growth.

DAGHER: It's really a big physics experiment.

What you try to do is try to get as much valuable data as you can at a small scale.

Is it 500-year?

It's gonna be 50-year.

O'BRIEN: Habib Dagher is executive director of the University of Maine's Advanced Structures and Composites Center.

He and his team are deploying a unique wind and wave simulator to test a scale model of a floating hull for wind turbines called VolturnUS.

DAGHER: We have load cells on the very top and bottom of the tower that tell us how much stress the tower is really seeing at that time.

O'BRIEN: The base of the full-size version will be made of concrete, and inside some of the hulls are counterweights attached to springs and actuators.

They are designed to negate the motion of the rolling sea.

DAGHER: You want to make sure it doesn't move too much.

So we're trying to minimize the motions at the turbine level and we're trying to reduce the pitch of the hull so it doesn't pitch too much over.

O'BRIEN: In 2013, they moored a floating 20-kilowatt one-eighth-scale model offshore for more than a year.

It got hammered during the long Maine winter, but never tilted more than five degrees.

Habib hopes to have a bigger, 11-megawatt turbine floating in the next few years.

DAGHER: So you want to make it lighter.

You want to make it easier to build.

So it's not just about designing something and making sure it works.

You got to figure out how to build it.

How to build it in an automated fashion.

We built the lab to try to answer those questions.

O'BRIEN: The allure of offshore floating wind is multifaceted.

The turbines are built onshore, reducing construction cost and environmental impact.

They can be towed to wherever the wind is more consistent, but the water too deep for fixed-bottom installations.

You can go 20 or 30, 40 miles offshore.

You can't do that with fixed-bottom ones.

You can put them in places where people can't see them and you can design them to put them in places where you minimize the impact on the environment-- the birds, the bats, and the fisheries and the mammals.

It gives you a lot more places to work with.

O'BRIEN: Floating offshore turbines also make it possible to develop wind energy on the west coast of the U.S., where the waters are precipitously deeper.

DAGHER: Within 50 miles of the U.S. coasts-- both east and west coast-- there's enough offshore wind capacity, theoretically, to power the country four times over.

O'BRIEN: But even if there is, in fact, enough wind, it alone won't be enough.

LOTT: So when I think about a zero-carbon grid and how we get to zero-carbon electricity, I think of it as a team sport.

You need a lot of different types of technologies all playing together if you want to win the game.

So you're going to have variable renewables, you're going to have wind and solar.

So when they're around, they're cheap, that's great.

But they fade sometimes-- the wind goes away, the sun sets.

So you complement them with other team members, like energy storage.

O'BRIEN: So how best to give electricity some shelf life?

Batteries.

The challenge is making them big enough and cheap enough to work at scale.

Yet-Ming Chiang is a professor in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering at M.I.T.

and co-founder of a company called Form Energy.

He's aiming to eliminate some of the gaps in energy availability when the weather isn't right for solar or wind.

CHIANG: What you see are gaps of several days.

We're now able to tackle those multi-day intervals, those 100-hour intervals.

And I want to point out that this is something that just a few years ago was considered impossible.

O'BRIEN: For the past 30 years, researchers have focused on lithium-ion battery technology.

The chemistry enables a high energy density.

Powerful for their size and weight, they are perfect for laptops, phones, and cars.

But they're not well suited for multi-day storage on the grid.

To compete with a natural gas power plant, a 100-hour battery pack must cost no more than $20 per kilowatt-hour.

CHIANG: But if we take a lithium-ion battery pack, the cost of that pack today is about $200 per kilowatt-hour.

In order to do multi-day storage, we have to have batteries that cost about one-tenth or less than that of today's lithium-ion battery packs.

O'BRIEN: So they found a novel way to harness the energy released when air interacts with iron.

It's the power of rust.

That's right, rust.

It's called an iron-air battery.

Iron-air batteries were, you know, first studied back in the '60s.

O'BRIEN: At that time, no one saw a practical application for a very cheap, very heavy battery.

The grid may be the problem this solution was waiting for.

Air is still free.

(laughs) And iron is one of the most widely produced, lowest-cost materials in the world.

So the iron-air battery is the lowest-cost rechargeable battery chemistry that we know of today.

O'BRIEN: The battery contains an iron metal anode and an air-breathing cathode.

They sit in an electrolyte solution, a permeable separator between them.

When the iron is exposed to the oxygen in air, it triggers a chemical process called oxidation.

We call this rust.

That oxidation process releases electrons that are separated and sent to the grid-- electricity when the demand exceeds renewable production.

When there is excess power from wind or solar, the process is reversed-- electrons flow in, releasing the oxygen, causing the iron to "unrust."

CHIANG: We put in electricity, we provide electrons to that iron electrode and turn it back into iron metal.

That's why we refer to the, you know, iron-air battery as the rusting and unrusting of iron, you know, carried out in a very intentional and deliberate way.

So these are full-scale iron-air batteries.

O'BRIEN: Form Energy co-founder and chief technology officer Billy Woodford...

There are oxygen bubbles.

O'BRIEN: ...showed me what the batteries look like.

And these have got four of those iron anodes inside of them.

O'BRIEN: He says their iron-air batteries are working just fine in the lab, but they haven't been tried on the grid yet.

WOODFORD: We need to scale up the manufacturing of this and really build the next generation of larger systems and deploy them.

And that really brings us to utility-scaled systems.

O'BRIEN: They plan on building their rust batteries in the Rust Belt, where the infrastructure and transportation network are already tailor-made for it.

The first plant will be built beside the Ohio River in Weirton, West Virginia, 750 good-paying jobs promised in a place of broken promises.

CHIANG: And so this will, you know, create real manufacturing jobs in parts of the country that have seen a great loss of jobs from, you know, traditional industries, and may not have seen themselves as part of this green revolution.

O'BRIEN: So the road to zero will pass through an old steel town in the heart of coal country.

Now there's some irony.

Batteries are just one storage idea.

There are many other technologies in development globally.

LOTT: The point of energy storage is saying, "You know what?

"I can produce electricity right now, but I don't need it.

"Well, let me hold on to it.

Let me put it in a savings account and cash it out later."

And then you complement those technologies with firm dispatchable power, which is a nerdy way of saying something that's around 24/7, 365.

This is things like big hydro power plants, and it's things like nuclear power and geothermal power-- power plants that are around when our wind and our solar and our batteries aren't quite enough to keep the lights on and prices low.

O'BRIEN: Experts say that current nuclear and hydroelectric power are important energy sources to maintain, but are impractical to grow much in time to reach our 2030 goal.

Geothermal may be a different story.

♪ ♪ Welcome to California's Salton Sea, one of the largest geothermal fields in the world.

It's renewable, carbon-free, and it's always on.

So exploring new ways to tap into this resource is now a very hot field.

Geothermal is the residual heat left over from the formation of the planet and from the decay of radioactive particles deep below the Earth's surface.

At a geothermal electric power plant, they drill down far enough to reach very hot water, a source of steam to generate power.

Another well injects the water back into the ground.

Historically, geothermal power has only been practical in seismically active places like this, where fault lines allow lots of hot water to rise relatively close to the surface.

Elsewhere, adequate heat is found at much greater depth.

So that's going down 10,000 feet.

JEFF TESTER: 10,000 feet, right.

It's not just, we drill a well and we're done.

We have to know what's going on under the ground.

You want to listen to the system, you want to have it talk to you.

O'BRIEN: Cornell University engineer Jeff Tester is pushing new ways to harness geothermal heat to generate electricity.

TESTER: If we could drop the costs of drilling to a very, very low value, and if we could use our knowledge of the subsurface in a way where we can engineer systems effectively, I think we certainly could do it.

We're not there yet, though.

O'BRIEN: Jeff Tester has led the charge developing something called enhanced geothermal systems, or E.G.S.

The idea: drill two deep wells into hot rock.

If the rock is not naturally permeable, fracture it in between to create an artificial reservoir, and then pump water into the cracks.

It returns to the surface hot enough to generate electricity.

If the technique proves out, it could make geothermal power generation possible almost anywhere.

But the cost of drilling must drop dramatically.

And once again, an ironic twist: the shale fracking boom-- responsible for producing so much oil and gas-- may have put this zero-emissions technology within reach.

CINDY TAFF: If we can crack the nut on this low-temperature geothermal, we can put it anywhere.

O'BRIEN: Petroleum engineer Cindy Taff is a 36-year veteran of the oil business.

Now she is C.E.O.

of Houston-based Sage Geosystems.

Near McAllen, Texas, they're drilling down on a geothermal concept that they hope will close the business case on E.G.S.

TAFF: That's the most important part, is, we have to get it cost- effective to wind and solar.

O'BRIEN: Conventional geothermal power plants must harvest underground water between 300 and 700 degrees Fahrenheit.

Cindy says Sage's design is targeting rock that is 30% cooler.

A key feature: this small, desk-sized turbine.

Instead of spinning the blades with steam from water, it uses carbon dioxide under pressure inside a closed loop.

In a separate pipe, water is pumped into fractured cracks in the rock.

Now hot, the water flows into a heat exchanger, raising the temperature of the CO2.

At around 88 degrees Fahrenheit-- less than half the heat required to boil water-- the CO2 can become "supercritical," meaning it has properties of both a gas and a liquid, and it is able to spin a high-RPM turbine.

TAFF: What we're excited about with this supercritical CO2 turbine is that it is double the efficiency of converting that heat to electricity.

O'BRIEN: Sage envisions an array of about 18 wells spaced roughly ten feet apart; combined, able to produce more than 50 megawatts.

If it works as they hope, enough to power more than 40,000 homes.

TAFF: What we're trying to do is turn geothermal from an art into a science.

O'BRIEN: One of Sage's partners lives nearby.

JAMES MCALLEN: Being a good steward of the land is, is making sure that the land is sustainable.

O'BRIEN: James McAllen is the manager of land his family has owned since 1791.

MCALLEN: There's a lot of things around me every day built by my ancestors, by my dad, by my grandfather.

Fences that were built by my great-grandfather.

So there's little reminders everywhere of people that have come before me.

O'BRIEN: He may be steeped in family history, but James is a forward-thinking steward of their land.

He has installed a solar array to sell electricity back to the grid, and now Sage is poised to drill wells on his property.

MCALLEN: You have to look forward, because if you don't look forward, you're not going to have this for very long.

Yeah.

So, and that's what this geothermal project's all about, is looking forward.

I think it's exciting that we're getting into something that I think is now the next level.

Mm-hmm.

I think it's a game-changer.

LOTT: So there's two things going on with power that we need to make sure we understand.

The first is, as we go to net zero, we need our electricity, our power plants, to be zero-carbon.

The second is, we're going to need more of them, because in our homes, our cars, a lot of the economy, we're going to use more electricity.

So we need more electricity and we need it all to be clean at the same time.

So if we have all these technologies on the field together, we get affordable, reliable, zero-carbon power.

If we take any one of these different teammates off the field, we won't win the game.

We end up with unaffordable or unreliable power.

♪ ♪ O'BRIEN: Many of the technologies to get us to net-zero emissions by 2050 are already here, and many more are well along in their development.

But as I discovered on the road with the Ford Lightning, there are still some speed bumps left to navigate.

The technology's existence is only half the battle.

You have to strategize when you're doing a long trip with an electric vehicle.

It makes you think a little more about your trip than you would otherwise.

♪ ♪ Ford loaned me the truck for a weeklong test drive.

Producer Will Toubman and I decided to stress-test the E.V.

charging network, so we drove the Lightning from the Boston area to Orono, Maine, to film that floating wind turbine prototype.

Ford promotes the truck as a backup power supply at home.

But on the road, getting electricity into the vehicle quickly can be a challenge.

We are headed for Portland, which will get us there right around 6:00 p.m. Good time to get a bite.

There's a fast charger there.

We slogged through some traffic, arrived at the fast charger, plugged in, and went to dinner.

Returned 90 minutes later.

The fast charger was set to turn off after one hour.

We needed more than an hour.

As it turns out, we currently have 123 miles of range and we have 133 miles to go.

We re-upped, plugged in, and waited: a watched pot of electrons.

We've been charging now for 30 minutes.

We have increased our range by 33 miles.

So about a mile a minute.

Nothing fast about this fast charger.

A dozen unused Tesla superchargers across the lot, incompatible with the Lightning, seemed to gloat in silence.

We resumed our journey with a promise of 153 miles of range.

A few hours and 133 miles later, we arrived at the only fast charger I could find in Bangor, at a car dealership.

This could be it.

O'BRIEN: It was about 11:00 p.m., we had only about 20 miles of range remaining, and we were in no mood for this.

Okay, so it says cash only.

It's the right kind of charger.

Let's see if I put a card in the mix here, if it will do anything for me.

"Swipe error."

Oh, boy.

So, uh...

I think we're seeing the problem here, aren't we?

Plan B: a charger at another car dealership nearby.

So, let's pull in, see what this looks like.

♪ ♪ Oh, no.

"Not in service."

Come on.

Looks like it's brand-new or something.

Supposedly there was another one here.

Supposedly.

And it too is, looks like it's brand-new and still not online.

So we've got two chargers coming to a dealership near you soon.

Again, not much help to us now with 18 miles of range at 11:23 at night.

O'BRIEN: Plan C: a slow charger a few miles away at a Maine Department of Transportation maintenance yard.

Hopefully this thing works.

Pop this bad boy in.

And let's make sure we're charging.

Yes, we are.

We are charging.

(chuckles) O'BRIEN: We stopped to charge eight times.

The nearly 500-mile round trip took twice as long as it would have in an internal combustion vehicle.

And there were a lot of mental gymnastics.

(echoing): 13 miles per hour...

Ten hours or so... 46 kilowatts...

It will be 90% full... 30 miles and change of range... 19 kilowatt-hours...

I feel like we've learned about nine lessons in the last 24 hours about how not to do this.

Since 2010, Americans have bought about three-and-a-quarter million plug-in hybrid and battery electric vehicles.

The government goal by 2030: half of new cars sold will be electric.

So, the charging infrastructure will need to grow fast to keep up.

Across the country right now, there are more than 130,000 publicly available E.V.

chargers.

The 2030 goal: a half-million public chargers, a nearly fourfold increase.

Engineers and entrepreneurs are seeing opportunities.

We found one company that is installing chargers on utility poles, just one clean-tech innovation amid thousands that are bubbling up with possible solutions.

CHIANG: These are all entirely new industries that are being created.

And, you know, investors want to be part of this new industrial revolution, as it were-- the Green Industrial Revolution.

O'BRIEN: A green industrial revolution: it's a reminder that this is how we evolve.

Humanity has made big energy transitions before: from wood to coal to oil.

And oil is just what's familiar now.

Is it natural to, like, dig up dead dinosaurs and burn them in our kitchen in 2022?

This isn't ancient Mesopotamia.

There's better ways to cook.

There's better ways to heat up hot water and provide heating and air conditioning to our homes.

O'BRIEN: The transition from fossil fuels to renewables is all but inevitable.

After all, the wells will go dry one day if we keep pumping.

And do we really have that luxury?

GALARZA: Climate change is not a crisis for the planet, it's a crisis for us as human beings.

It's an existential crisis.

Because if we don't do something, the Earth is just going to shake us off like fleas and move on.

O'BRIEN: But change can be frightening when you are in the throes of it.

And fear can beget apathy in the absence of good leaders.

WILSON: If we stop the methane, very quickly, it can make a huge dent.

It's the low-hanging fruit in solving the climate problem.

The only thing we lack is the political will.

O'BRIEN: And yet there are some signs of a course correction.

The U.S. now has climate and infrastructure laws that set things in motion.

But do we need to go faster?

We don't have a sense of urgency yet enough to do this.

When we had to fight in World War II, there was no question things were going to happen quickly.

I think we just have to get down to business right away.

O'BRIEN: A route to zero is clearly marked.

First, focus on energy efficiency, and then plug as many things as possible into the grid while pulling fossil fuels off the grid and adding zero-carbon power production as fast as we can.

It'll get us close to 50%.

We hope it'll get us all the way to 50% by 2030, but it'll put us on the pathway we need to be on to get to net zero by 2050.

O'BRIEN: No breakthroughs required for that.

At the same time, push for the innovations that can tackle the thorniest problems, like industry, aviation, shipping, and agriculture, by 2050.

Do I know that we're going to get to 50% reduction by 2030?

No.

I think it's going to be close.

We could overshoot it if a couple of things go right.

We might undershoot it.

But when I look back at what we thought we'd be doing by this time, we're so much further along the road.

This all gives me cause for a lot of optimism.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S50 Ep6 | 29s | Here’s how the U.S. could reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. (29s)

Chasing Carbon Zero Sneak Peek

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S50 Ep6 | 1m | A new film from NOVA examines technologies that could get us to carbon zero by 2050. (1m)

How Heat Pumps Can Help Cities Lower Carbon Emissions

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S50 Ep6 | 4m 17s | Landlords are switching from gas furnaces to heat pumps to reduce their carbon footprint. (4m 17s)

Why Induction Stoves Are Better for You and the Environment

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S50 Ep6 | 2m 56s | Induction stovetops are an energy-efficient alternative to traditional gas stoves. (2m 56s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- Science and Nature

Capturing the splendor of the natural world, from the African plains to the Antarctic ice.

Support for PBS provided by:

Additional funding is provided by the NOVA Science Trust with support from Anna and Neil Rasmussen, Howard and Eleanor Morgan, and The Arthur Vining Davis Foundations. Major funding for NOVA...